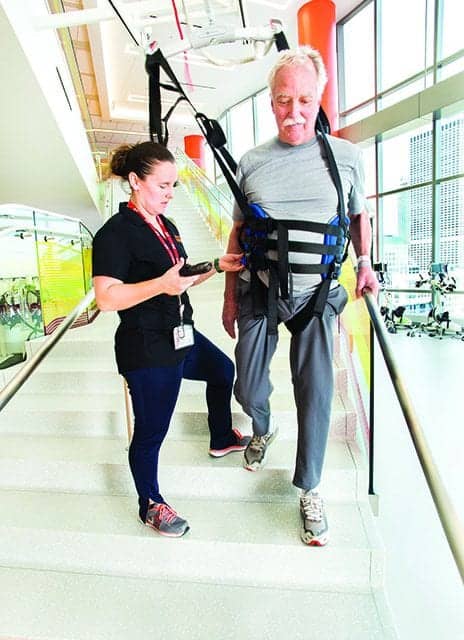

A physical therapist at the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab leads gait training for a patient. The patient’s weight is shared with the lift system, which decreases support as the patient’s ability increases.

by Kate Drolet, PT, DPT, NCS, CLT-LANA, and Kristine Buchler, PT, DPT

In the heart of Chicago’s bustling Streeterville neighborhood lies Shirley Ryan AbilityLab, formerly the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago. In March 2017, the organization opened a $550 million, 1.2-million-square-foot facility as a “translational” research hospital in which clinicians, scientists, innovators, and technologists work together in the same space, surrounding patients, discovering new approaches, and applying (or “translating”) research in real time.

Within the 27-floor rehabilitation hospital, this translational model plays out in the five ability labs—applied research and therapeutic spaces—each focused on specific functional outcomes. Together, therapists and researchers offer evidence-based interventions for a minimum of 3 hours each day. The goal: better, faster outcomes for patients.

For instance, the Legs + Walking Lab is a dynamic, two-story space designed for inpatients to focus specifically on gait training, stairs, balance and strengthening related to lower-body impairments due to brain injury, stroke, spinal cord injury, or diseases of the nerves, muscles, or bones.

While this list is not all-encompassing, one of the most prevalent diagnoses treated in the Legs + Walking Lab is stroke—and one of the most common therapies offered for post-stroke patients is gait training.

At the heart of Shirley Ryan AbilityLab’s efforts to lead patients toward an optimum outcome are more than 200 active clinical trials and research studies aimed at improving recovery post-stroke. Interdisciplinary teams consisting of physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech-language pathologists, doctors, nurses, researchers, psychologists, and social workers work together with patients to identify specific goals and then outline a treatment program aimed at maximizing functional independence.

Patients also are referred to therapists based within the various ability labs who specialize in areas such as gait training, vestibular therapy, task-specific upper extremity training, aphasia, dysphagia, cognition, and pain. These therapists work closely with the primary therapists to identify the proper dosage, intensity and duration of sessions needed to facilitate neural reorganization for their specific interventions.

A physical therapist at the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab leads treadmill training for a patient recovering from stroke. A harness system is used for safety and fall prevention.

Gait Training Out of the Gate

In the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab Legs + Walking Lab, gait therapists focus on promoting locomotor recovery for patients post-stroke. The primary physical therapists refer patients to gait therapy if walking goals are indicated, usually soon after completion of the initial evaluation.

Why is it so important to commence gait therapy soon after evaluation? Research indicates that earlier and more intensive rehabilitation post-stroke yields a quicker return to independent ambulation and improved functional mobility.1 As a result, getting patients up and moving as quickly as possible is the expectation once vitals are stable. If gait training is indicated but is not yet safe due to unstable vitals or orthostatic hypotension, patients still often will be referred to gait therapists to assist with tolerance to upright training using the tilt table or stander before progressing to ambulation.

The literature has shown that repetition, intensity, and task-specificity are important principles of neuroplasticity to consider for gait recovery post-stroke.2 Gait therapists work with the primary physical therapists to promote large amounts of high-intensity, task-specific gait training with each patient to facilitate plasticity of both neuromuscular and cardiopulmonary systems. Walking practice is prioritized during most physical therapy sessions to achieve sufficient dosage and repetition.

Although conventional practice often involves spending time on multiple different interventions, research has indicated that high-intensity gait training also can translate to improvements in non-walking tasks such as balance and transfers, despite not focusing on those tasks.2-4

Using the Latest Specialized Equipment

At Shirley Ryan AbilityLab, therapists are fortunate to have a great deal of specialized equipment readily available to assist with implementing gait interventions with stroke survivors.

Therapists often are helping patients get up for the first time after their strokes. This may require a great deal of assistance. Because the safety of both patients and therapists is always a priority, the Legs + Walking Lab is outfitted with body-weight supported treadmills and overhead gait tracks for mobilizing lower-level patients.

Even for patients who may not require body weight support, harness systems are still used for safety and fall prevention when performing treadmill training or when challenging patients during higher-level balance activities overground. There is also a suspension system over the staircase in the Legs + Walking Lab, which provides a safe method for patients to relearn stair climbing.

In terms of modality of walking practice, the evidence is unclear as to whether treadmill or overground training is more effective in facilitating locomotor recovery. Therefore, therapists must consider how best to achieve the principles of neuroplasticity when choosing the modality for gait training. For lower-level patients who require more assistance, this generally means an increased, early focus on body weight-supported treadmill training early on to maximize repetition and intensity. Then, as patients progress, therapists can integrate overground gait training more frequently to promote increased task specificity. For patients who require less assistance, treatment sessions are generally more evenly divided between treadmill and overground gait training.

Although the Legs + Walking Lab has a robotic treadmill device, it is not commonly used during stroke rehabilitation. Evidence indicates that robotic-assisted gait training is less effective than therapist-assisted gait training in improving walking ability post-stroke.5,6 However, there are certain circumstances in which robotic-assisted gait training may be indicated to reduce the physical burden placed on therapists when gait training with stroke survivors who do not have much motor return and require a significant amount of assistance to advance both legs.

In addition, therapists have access to various exoskeletons for patients in the Legs + Walking Lab that are used in conjunction with treadmill and overground gait training due to limited research using exoskeletons in the post-stroke population.

The Shirley Ryan AbilityLab’s Legs + Walking Lab is designed for patients and research participants with diagnoses affecting lower-body function due to brain or spinal cord injury and diseases of the nerves, muscles, and bones. Researchers and clinicians focus on advancing trunk, pelvic, and leg function, movement, and balance in this dynamic, applied research and therapeutic space.

When to Challenge, When to Modify

When progressing gait interventions for patients post-stroke, the initial focus is on decreasing the amount of body weight support or level of assistance as able. Once patients begin to require less assistance and are able to perform stepping without assistance, therapists can begin to progress the challenge of the task. Evidence suggests that variability and error play an important role in motor learning and can contribute to improvements in locomotor function in stroke survivors.3,5-8 Therefore, these principles are crucial to integrate into gait interventions. This is done by allowing kinematic variability and providing variation to the task and environment, incorporating activities such as multi-directional stepping, obstacle negotiation, uneven surfaces, or changes in gait speed. Therapists can then adjust the level of challenge depending on patient response. If a patient does not make any errors, it generally means that the task is not challenging enough and should be progressed. Conversely, if a patient demonstrates several consecutive errors and is unable to correct without assistance, that generally indicates that the task is too challenging and should be modified.

Throughout the progression of gait training, the physical therapists monitor intensity and exercise tolerance based on heart rate and blood pressure response to activity, rating of perceived exertion (RPE), and verbal and nonverbal signs and symptoms if a patient has cognitive and/or communication deficits. It is also important to evaluate progress in order to guide clinical decision-making and determine whether the interventions are effective. This is done using various outcome measures, such as the Functional Independence Measure, 6 Minute Walk Test, 10 Meter Walk Test, Berg Balance Scale and Functional Gait Assessment, in addition to clinical judgment and observation. At times, primary physical therapists or lab therapists who specialize in gait training may need to decrease the frequency of gait training sessions if a patient is not responding well, if progress is limited, or if the goals of a patient’s stay shift to family education in preparation for discharge.

The Next Chapter: Therapy After Discharge

After patients discharge from the hospital, they will likely continue at a Shirley Ryan AbilityLab DayRehab or Shirley Ryan AbilityLab outpatient location. There, they will receive additional therapy, similar to the inpatient setting, while commuting to and from their homes. Therapists at DayRehab and outpatient locations continue to promote high-intensity gait training with an emphasis on home exercise programs, community reintegration, and return to work, when appropriate.

Some patients travel long distances for the intensive inpatient therapy program, so outpatient therapy at a local clinic or hospital may be the only option close to home after discharge. For these patients, inpatient therapists at the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab train families and personal caregivers to implement the principles of neuroplasticity and advocate for high-intensity gait training after discharge.

Regardless of a patient’s particular journey, the message for post-stroke recovery is clear: the more walking, the better. RM

Kate Drolet, PT, DPT, NCS, CLT-LANA, earned a bachelor’s degree in exercise physiology and a doctorate in physical therapy from Marquette University in Milwaukee. She is a Board Certified Clinical Specialist in Neurological Physical Therapy and a Certified Lymphedema Therapist through the Lymphology Association of North America. She practices at the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab (formerly Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago) and specializes in gait training for patients with neurologic conditions in the inpatient setting.

Kristine Buchler, PT, DPT, earned a bachelor’s degree in kinesiology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and a doctor of physical therapy degree at Northwestern University. She currently practices as a physical therapist at the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab and specializes in gait training for patients with neurologic conditions in the inpatient setting. For more information, contact [email protected].

This article appears in the January/February 2019 print issue of Rehab Management with the title, “Walk This Way.”

References

1. Cumming TB, Thrift AG, Collier JM, et al. Very early mobilization after stroke fast-tracks return to walking. Stroke. 2011;42(1):153-158. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.110.594598

2. Hornby TG, Straube DS, Kinnaird CR, et al. Importance of specificity, amount, and intensity of locomotor training to improve ambulatory function in patients poststroke. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2011;18(4):293-307. https://doi.org/10.1310/tsr1804-293

3. Hornby TG, Holleran CL, Hennessy PW, et al. Variable intensive early walking poststroke (VIEWS). Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2015;30(5):440-450. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968315604396

4. Straube DD, Holleran CL, Kinnaird CR, Leddy AL, Hennessy PW, Hornby TG. Effects of dynamic stepping training on nonlocomotor tasks in individuals poststroke. Phys Ther. 2014;94(7):921-933. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20130544

5. Hornby TG, Campbell DD, Kahn JH, Demott T, Moore JL, Roth HR. Enhanced gait-related improvements after therapist- versus robotic-assisted locomotor training in subjects with chronic stroke. Stroke. 2008;39(6):1786-1792. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.107.504779

6. Hidler J, Nichols D, Pelliccio M, et al. Multicenter randomized clinical trial evaluating the effectiveness of the Lokomat in subacute stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2009;23(1):5-13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968308326632

7. Holleran CL, Straube DD, Kinnaird CR, Leddy AL, Hornby TG. Feasibility and potential efficacy of high-intensity stepping training in variable contexts in subacute and chronic stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2014;28(7):643-651. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968314521001

8. Reisman DS, McLean H, Keller J, Danks KA, Bastian AJ. Repeated split-belt treadmill training improves poststroke step length asymmetry. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2013;27(5):460-468. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968312474118