|

Back when Indianapolis rehabilitation provider Mike Ploski, PT, ATC, OCS, first entered the profession 18 years ago, it was common practice for orthopedic surgeons to immobilize the repaired legs of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction patients by casting them for approximately 6 weeks. Usually, though, spending that much time in a cast allowed muscles to atrophy, resulting in loss of range of motion and strength.

Now, however, greater understanding of tissue healing properties and rehab principles (coupled with advances in surgical techniques and materials) have rendered 6 weeks of casting obsolete. Consequently, therapists like Ploski can begin the postoperative rehabilitation process within a matter of days following surgery—a huge benefit to ACL patients. But this earlier rehab also increases the demand for patient safety. To help him deliver precisely that (along with greater efficacy of therapy), Ploski has brought aboard his practice a variety of modalities geared specifically for treatment of the lower extremities.

“With the resources now available to us, it’s the rare patient who today won’t relatively quickly recover from surgery and regain function in the lower extremity,” says Ploski, clinic director of Memphis-based Physiotherapy Associates, a leader in outpatient orthopedics with 500 clinics nationwide and a reputation for delivering high-level care. “Patients are making faster and better headway because of these.”

STEP LIGHTLY

AN INTRIGUING TECHNIQUE |

|

|

Many therapists now say they routinely include Kinesio taping in their rehabilitation of the lower extremities.

This intriguing technique entails taping over and around muscles by means of special elastics (stretchability of 130% to 140% of unstretched original length) in order to assist and give support (or to prevent overcontraction) while at the same time providing free range of motion. This blend of support restrictiveness and motion freedom allows the body’s muscular system to heal itself biomechanically. Specifically, it alleviates pain and facilitates lymphatic drainage by microscopically lifting the skin. The tape forms convolutions in the skin, thus increasing interstitial space, with the result being that pressure and irritation are taken off the neural and sensory receptors, thereby alleviating pain; meanwhile, pressure is gradually taken off the lymphatic system, allowing it to channel more freely. The special tape used with the Kinesio technique can be adapted for other forms of therapy, including cryotherapy, hydrotherapy, massage therapy, and electrical stimulation. The technique was developed in Japan nearly a quarter century ago by physician Kenzo Kase.1 — RS REFERENCE

|

Agreeing with that assessment is Jim Beese, PT, ATC, MOMT, owner and manager of Performance Physical Therapy in Bridgeview, Ill, and a partner in four other physical therapy offices in the greater Chicago area. “Today’s rehab modalities are allowing us as physical therapists to keep pace with the advances coming out of the field of orthopedic surgery,” he says.

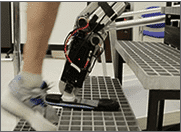

Beese—who sees many postoperative and postinjury lower-extremity cases, thanks in part to his role as an official team therapist for the Chicago Fire (the Windy City’s professional soccer team)—believes it is crucially important to work as fast as possible at getting these patients’ feet, legs, and joints able to once again bear weight while, at the same time, reinforcing their proper walking patterns. This, he says, requires a controlled weight-bearing progression, which he contends is best achieved with the aid of unweighing, or gravity-unloading, systems.

Unweighing can be achieved in water or on land. A proponent of aquatic therapy, Beese is having a therapy pool installed at his newest clinic, slated to open later this year at Chicago Fire Stadium, in Bridgeview. “Therapy pools are an excellent early rehabilitation tool,” he says. “The buoyancy of the patient’s body in water provides the necessary unweighing, and you can combine this with an underwater treadmill or you can introduce resistance by streaming a current of water at the patient.”

Unweighing on land can be accomplished using sling-hoist devices—meant to be positioned above a treadmill (ideally, engineered with a flexible yet stable surface that absorbs and dissipates impact shock). The user is suspended in a way enabling him to walk without developing antalgic gait. “The amount of body weight that can be offloaded in an exacting, controlled manner with these systems ranges from 20% to 75%,” says Beese.

One make of unweighing system found in Beese’s practice incorporates a dynamic suspension system that accommodates up to 4 inches of vertical displacement while maintaining a consistent level of unweighing. Additionally, it features single-point suspension to allow unrestricted pelvic rotation so that the patient can engage in side-stepping, retro-walking, and turning as he ambulates along the treadmill platform (should pelvic stabilization be desired, retention cords can be attached to the sides of the support vest worn by the patient; these secure to the system’s frame and can be adjusted for the specific degree of stabilization sought).

Beese views biofeedback systems in general as advantageous for lower-extremity muscle recruitment. “They are invaluable for kinesthetic and proprioceptive training, especially when they are paired with computer technology that provides visual biofeedback,” he says. “One such biofeedback system we use consists of two force plates that let the patient work on right-to-left weight-shift and on maintaining equal weight-bearing while in standing or squatting positions. It also has programs for simulating downhill slalom skiing. Another system we have is essentially an electrogoniometer that attaches to either the knee or shoulder; it has a computer program that challenges the patient to maintain specific positioning while performing various functional activities. The benefit of these systems is we’re able to help the patient achieve faster return to kinesthetic awareness, faster improvements in balance, and faster gains in motor planning and reactive timing.”

An intriguing biofeedback system used in Europe—now making its way into the United States—consists of a flexible force-sensing shoe insole designed to measure the amount of weight applied to the plantar surface of the foot. A miniature portable control unit worn around the ankle receives and analyzes the data collected, and provides real-time auditory indications of correct or incorrect gait performance. This device makes a useful tool for teaching and promoting specific weight-bearing skills, and for testing a patient’s overall progress and ability to maintain a weight-bearing range; meanwhile, an alarm feature alerts the user or therapist (or both) when weight-bearing exceeds a set value, as a way of preventing complications during the rehabilitation process.1

Complications are always a concern, no matter the modality used. Thus, Beese seeks to minimize the risk of reinjury or other setbacks by starting many of his therapy sessions with a 4- to 5-minute application of cold laser treatment or, for larger areas of swelling or bruising, monochromatic infrared energy. “These modalities use light energy to work at the cellular level and speed up tissue healing via metabolic processes,” he says. “They help improve microcirculation and decrease inflammation at the surgical site. Very helpful for patients with significant ecchymosis.”

LOW TECH, HIGH YIELD

An effective intervention for addressing plantar fasciitis and Achilles tendonitis (both of which can be very difficult to treat with conservative measures) is augmented soft tissue mobilization. Soft tissue mobilization encompasses myofascial release, cross-friction, and other massage-oriented techniques intended to free up scar tissue and fascial restrictions of the sort that can adhere right down to the bone and prevent the smooth gliding of tendons. Instrument-assisted soft tissue mobilization is employed extensively by Michael Kim, MPT, CHT, co-owner of Summit Rehabilitation Associates in Spokane, Wash.

“I’ve used soft tissue mobilization for a long time, but about 3 years ago I switched over to an instrument-assisted form of it,” Kim says. “With the instruments there is less wear and tear on my hands, so I’m able to palpate tissues and mobilize joints all day long without my hands becoming fatigued or sore.”

Kim says he likes the way instrument-assisted soft tissue mobilization resolves pain quickly and affords a swifter return to function. “Last week, for example, I worked with an Olympic-caliber heptathlete at Washington State University who had developed plantar fasciitis,” he shares. “She was in pain whenever she ran, and it was adversely affecting her ability to engage in high jumps and hurdling. The university has a well-equipped training room, and they tried all the modalities and normal conservative treatments available in physical therapy, but didn’t see much improvement in the patient. I did two treatments with instrument-assisted soft tissue mobilization, and she was able to comfortably run again. Her improvement was remarkable.”

Sometimes, low-tech approaches are all one needs to help a lower-extremity patient, as Ploski can attest. A few such modalities he embraces include therapy balls and stretch bands. “[Therapy balls] have become more common in the clinic, but much more so in the home,” says Ploski. “Very affordable, they’re a nice piece of equipment for a patient to own. They’re also quite versatile—they don’t limit you to core stabilization trunk exercises.

“[Stretch] bands are great from the standpoint of giving patients basic resistance exercises they can perform at home,” he says. “They are most effective for the rehabbing of smaller joints that have less range of motion—such as an ankle, which will have maybe 50 degrees of ROM from the extreme of inversion to the extreme of eversion.”

Clearly, there are many options these days for rehabbing lower extremities. And, from the look of things, it could well be that those options will only grow and become better as time goes by.

Rich Smith is a contributing writer for Rehab Management.

REFERENCE

- International approvals: SmartStep, Amplatzer, CardioLife. Medscape Medical News, August 15, 2005. Available at: http:// www.medscape.com/viewarticle/511863. Accessed May 1, 2006.