When it comes to addressing muscle aches and pains, physical therapists have a variety of treatment options at their fingertips. Iontophoresis—the process of transferring a substance via direct current through the skin to the affected tissue—has long been a staple of rehab medicine for treating soft-tissue inflammation.

In fact, many professional trainers and athletes, including the US ski team and Olympic runners, use iontophoresis routinely. “They’ll carry units with them on the road and actually treat players between games because it’s rapid and noninvasive,” says Thomas M. Parkinson, PhD, a medical device and pharmaceutical products consultant, specializing in the development of novel oral and transdermal drug delivery systems, for a St Paul, Minn-based company. Previously, Parkinson was vice president of research and development and general manager for a Salt Lake City-based transdermal drug delivery systems firm.

Patrick Zerr, MS, PT, who runs Summit PT in Tempe, Ariz, uses the technique to relieve pain from conditions such as tennis elbow, carpal tunnel and other wrist injuries, lateral ankle sprains, and patellar tendonitis. He has also found iontophoresis to be effective after rotator-cuff repair. “I like to use it for areas that are inflamed or swollen that don’t have a lot of deep muscle tissue,” he says.

For example, Zerr used iontophoresis to treat a high-school basketball player who presented with a sprained anterior talofibular ligament. “It really helped speed up the recovery process for the athlete so that they could exercise without pain, build their strength back up, and tolerate more weight bearing,” he says.

MORE OPTIONS

There are many different medications and supplements that can be applied through iontophoresis, but therapists most commonly use dexamethasone sodium phosphate, an anti-inflammatory drug. Traditionally, dexamethasone is injected or administrated intravenously to patients, but using iontophoresis allows therapists to target the affected tissue directly while bypassing the rest of the body.

|

| Iontophoresis, a transdermal drug delivery system, is gaining popularity among both medical professionals and their clients as a preferred pain management tool. |

“They’re also doing it noninvasively, so you don’t have the problem with needle phobia or injecting large amounts of steroid into an area where it could cause tissue damage if it’s not done right,” Parkinson says. It also minimizes the side effects of a medication.

Although dexamethasone is the most common medication used, some therapists apply saline to soften scar tissue or acetic acid to reduce tissue calcification or even to address bone spurs in the heel. No matter what solution the PT uses, however, iontophoresis is often only one part of the treatment regimen, which includes massages, heat or cold packs, ultrasound, and strengthening and stretching exercises.

“All of these in conjunction will help the patient get back to normal as rapidly as possible,” Parkinson says.

The iontophoresis units themselves are fairly simple devices that require no calibration or testing. Other than ensuring the batteries are fresh and hold their charge throughout the treatment, there is very little maintenance involved.

While the basic technology has not changed much over the decades, improvements in the devices now give physical therapists smaller units and more options. “They have many more choices than they did, say 30 years ago, when there were basically only one or two types of products on the market,” Parkinson says.

Traditional models, about the size of a portable radio, were designed for in-house treatment. They allowed physical therapists to either adjust the settings to their own preference for each patient or use standard presets. Today, there are more flexible options, including rechargeable units, rechargeable batteries, and disposable units.

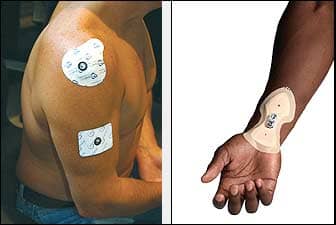

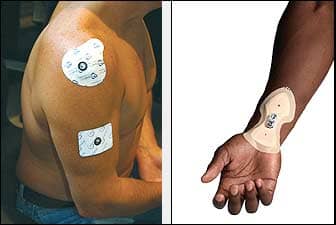

There is even an option that doesn’t require the patient to stay for the treatment cycle. “The whole unit is basically contained in one stick-on patch,” Parkinson says. “You simply activate the electrodes and then put it on the skin like a large Band-Aid, and the controller starts and delivers the programmed dose.”

Of course, as in-office treatments are typically short—usually between 12 and 18 minutes—the portable patches may not be practical for every office. Therapists may be concerned that the patch will fall off or that the patient may not get the full dose. “I don’t tend to think they’re as effective,” Zerr says. “They deliver the medication at a much slower rate.”

No matter what unit you choose, however, Zerr recommends choosing electrodes with softer material that is less likely to irritate patients’ skin. “The better the quality of the electrode, the better the results usually turn out to be,” he says.

EFFECTIVE TREATMENT

Iontophoresis has few contraindications, but the technique is not appropriate for all patients. For example, patients with pacemakers, defibrillators, or implantable drug-infusion pumps are not candidates, as these support systems may be sensitive to the electric current.

The technique also should not be applied to patients who are sensitive to the drug itself or to the preservatives in its formulation. It is also important to avoid damaged skin. “It’s really meant to deliver through normal skin tissue,” Parkinson says.

Some patients with sensitive skin may be susceptible to mild skin irritation or even mild burns. For this reason, iontophoresis should never be applied to already damaged skin. Those with fair skin are often more sensitive to the treatment, and Zerr lets these patients know the risk of skin burns in advance and works with them to weigh the benefits of the overall treatment.

In the end, every patient responds differently, so it is important to monitor the individual’s comfort level during treatment. “With some people, you can put the electrodes on and turn the machine on, and they can’t even feel it,” Zerr says. “With other patients, they feel it to an intensity level that is very uncomfortable. They can’t tolerate it.”

The expense of the treatment—which involves the use of costly electrodes—can also be a deterrent for some physical therapists. Cautioning that Medicare and other insurance carriers do not necessarily cover iontophoresis, Zerr recommends choosing patients carefully.

“If they’re really inflamed and other traditional ways of getting rid of that inflammation aren’t working, then I like to use it,” Zerr says. “I don’t typically use it as a first line of defense.”

He also makes sure that the affected tissue is no more than 1 cm below the surface. “If you can palpate the tissue that is irritated and painful, and you apply iontophoresis there, you’re going to see the success,” Zerr says. He also avoids large surfaces, such as the back or neck, as these areas are generally too broad for the treatment to be effective.

Another way to ensure effective treatment is to place the electrodes strategically. Iontophoresis involves placing two electrode pads on the patients—one medicated pad, and one dispersive pad. Zerr finds it most effective to place both electrodes within the same fascial envelope of the affected area.

For example, when treating patellar tendonitis, he has found that placing one pad on the affected area and one below the knee is more effective than placing the second pad above the knee on the thigh. “It seems to work better if you can keep both electrodes in the same area,” Zerr says.

While iontophoresis produces successful results for many patients, it’s not for everyone. Physical therapists should consider how it complements the other modalities they use within the practice and match the treatment to the patient. “It’s not a magic bullet,” Parkinson says. “Physical therapists should see how this fits into their whole treatment regimen.”

FUTURE APPLICATIONS

When iontophoresis products first garnered FDA approval, Parkinson says the industry focused on developing systems for the delivery of dexamethasone in physical therapy practices. Now that this technology has been fairly well established, he feels the next frontier will be developing broader pharmaceutical applications outside of rehab medicine.

For example, iontophoresis could have implications for patient-controlled analgesia, as it provides rapid, controllable, on-demand delivery without the use of a needle. “As technology has advanced to these smaller, more convenient, more efficient devices, iontophoresis is moving much more into the pharmaceutical industry as a mainstream drug-delivery system,” Parkinson says. “I think that’s where the future really lies.”

According to Parkinson, there are already more than 200 existing drugs that could be compatible with iontophoresis, and so the next phase would be developing ways to deliver these drugs effectively. This may involve other types of anti-inflammatory agents, such as ibuprofen, depending on the advantages that researchers discover.

“It’s pretty inexpensive to get a bottle of ibuprofen tablets and just take four a day,” Parkinson says. “But I think as the industry gets interested in iontophoresis as a mainstream delivery system, there may be reasons why this changes.”

Eventually, these advances may feed back into rehab medicine and influence how the technique is used in physical therapy practices. But in the meantime, iontophoresis continues to offer physical therapists an effective way to address soft-tissue inflammation.

“Being able to administer an anti-inflammatory drug together with all the other healing modalities is really advantageous,” Parkinson says. “Because if you can stop the basic process [of inflammation], then it makes it much easier for the tissue to get back to normal.”

Ann H. Carlson is a contributing writer for Rehab Management. For more information, contact .

For more information on iontophoresis, see our Expert Insight column by Thomas M. Parkinson, PhD consultant, Research and Business Development, with Hybresis by Empi.