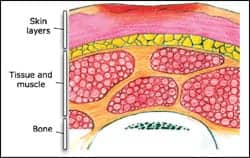

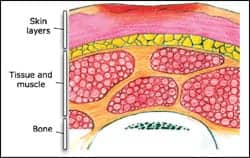

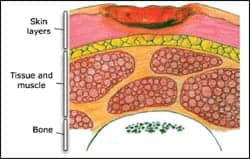

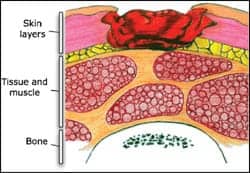

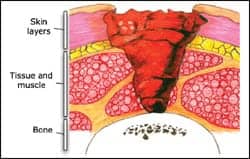

| PROGRESSION OF DECUBITIS ULCER |

|

| STAGE 1 |

|

| STAGE 2 |

|

| STAGE 3 |

|

| STAGE 4 |

| The Pressure Ulcer Prevention Project at the Division of Occupational Science & Occupational Therapy at the University of Southern California |

Pressure ulcers are a major health care problem in the United States, impacting quality of life and affecting both morbidity and mortality. The cost of healing a complex pressure ulcer may be as high as $70,000, not including the cost of pain and suffering.1 It is estimated that 2.5 million patients are treated for pressure ulcers in acute care facilities every year with an estimated cost of $11 billion per year.2

A pressure ulcer is defined as a localized injury to the skin and/or underlying tissue usually over a bony prominence, as a result of pressure, or pressure in combination with shear and/or friction. The National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel presented a redefinition of pressure ulcers and the stages of pressure ulcers in February 2007. The classification of deep tissue injury and unstageable pressure ulcers has been added to the original four stages, which have been clarified and redefined.

PRESSURE ULCER STAGES

Suspected Deep Tissue Injury: Purple or maroon localized area of discolored intact skin or blood-filled blister due to damage of underlying soft tissue from pressure and/or shear. The area may be preceded by tissue that is painful, firm, mushy, or boggy, warmer or cooler, as compared to adjacent tissue. This stage may be difficult to identify in patients with dark skin tones. A thin blister may develop over a dark wound bed; the wound may further evolve and become covered with eschar. Evolution may be rapid, exposing additional layers of tissue even with optimal treatment.

Stage I: Intact skin with nonblanchable redness of a localized area, usually found over bony prominences. Blanching may not be visible in darkly pigmented skin. The area may be painful, firm, soft, warmer, or cooler as compared to adjacent tissue.

Stage II: Partial thickness tissue loss that involves the dermis. It may also present as an intact or ruptured, open serum-filled blister, or as a shiny or dry shallow ulcer without slough or bruising.

Stage III: Full thickness tissue loss. Subcutaneous fat may be visible, but bone, tendon, and muscle are not exposed. Slough may be present but does not obscure the depth of the tissue loss. There may be undermining and tunneling.

Stage IV: Full thickness tissue loss with exposed bone, tendon, or muscle. Slough or eschar may be present on some of the wound bed and is often accompanied by tunneling and undermining. The depth can extend into the muscle and/or supporting structures, making osteomyelitis possible. Exposed bone and/or tendon is visible or directly palpable.

Unstageable wounds: Full thickness tissue loss where the base of the wound is totally obscured by slough or eschar, which prevents accurate staging. Stable eschar on the heels serves as “the body’s natural cover” and should not be removed.3

PREVENTION OF PRESSURE ULCERS

Pressure ulcers develop when persistent pressure over a bony prominence obstructs the capillary flow, resulting in tissue necrosis.4 They typically form on the back of the head, sacrum, heels, or elbows. As pressure ulcers can develop in 2 to 6 hours, early assessment and intervention are key to prevention.

The most widely used risk assessment tool is the Braden Scale, which evaluates the six most common risk factors and enables caregivers to rate the patient’s risk. The risk factors include immobility, incontinence, sensory deficiency, dehydration, inadequate nutrition, multiple comorbidities, and circulatory abnormalities.

A two-step assessment should be completed on every patient in the first 6 hours after admission. First, a skin assessment evaluating for pressure ulceration, and second, a risk assessment evaluating the potential for developing pressure ulcers.1

|

DRESSING TYPE |

THERAPEUTIC USAGE |

|

Gauze |

Good for packing dead space; Generally requires a secondary dressing; Need frequent dressing changes |

|

Transparent or polymer films |

Promotes autolysis; Suitable for Stage I and II ulcers; Used for noninfected wounds |

|

Hydrocolloids |

Promotes autolysis; Suitable for superficial and partial thickness wounds with minimum to moderate exudate |

|

Foams |

For partial to full thickness wounds with minimal exudate; Good for Stages II to IV; Provides moist environment and thermal insulation |

|

Hydrogels |

Promotes autolysis and a moist wound environment; Aids in pain control and decreased inflammation; Good for Stages II to IV with minimal exudate |

|

Alginates |

Highly absorbent; Good for partial and full thickness ulcers with moderate to heavy exudate; Good for packing tunnels, cavities, sinus tracts; Can stay in place up to a week; Requires secondary dressing |

|

Collagens |

Stimulates cellular migration and new tissue formation; Absorbent; Good for cavities and deep wounds |

|

Composite |

Combines the properties of several types of dressings; Use as a primary or secondary dressing; Good for partial to full thickness wounds with moderate to heavy exudate |

Subsequent evaluations should be done every 12 hours on high-risk patients, especially those with multiple comorbidities. For low-risk patients, subsequent evaluations should be made with each change in status, identifying new risk factors and implementing prevention strategies.1

Proper skin care includes minimizing skin moisture caused by incontinence, perspiration, or wound drainage; using a mild cleansing agent, rinsing thoroughly, and patting dry to avoid friction; moisturizing with lotion to minimize dryness; and protecting the skin with a topical moisture barrier and/or an absorbent underpad.

Patients are at risk for pressure ulcers if they are malnourished or dehydrated. The plan of care needs to include nutritional supplementation consistent with the patient’s needs and goals, and assisting with meals and hydration.

Changes in mental status and/or physical ability increase the risk for developing pressure ulcers. The focus of care is pressure reduction and/or redistribution. Reposition bed-bound patients every 2 hours and chair-bound patients every hour with weight shifts every 15 to 30 minutes.5 Pressure-reducing devices such as pillows and wedges increase comfort and decrease pressure on bony prominences when placing patients on their side. The head of the bed should not be elevated greater than 30° for extended periods. Use electrical lifts or draw sheets when repositioning patients to prevent friction/shear injuries.

Cushioning and pressure-reducing devices that redistribute the pressure exerted on the skin and subcutaneous tissue have led to improved outcomes in high-risk patients.4 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has divided these devices into three categories for reimbursement purposes. Group 1 includes devices that do not require electricity, such as air, foam, gel, or water overlay mattresses for low-risk patients. Group 2 devices are dynamic, powered by electricity, and include alternating and low air loss mattresses for moderate- to high-risk patients or those with full thickness pressure ulcers. Group 3 devices are also dynamic, powered by electricity, and include air-fluidized beds for patients with nonhealing full thickness pressure ulcers.5

Bariatric patients present unique challenges with maintaining skin integrity. Physical immobility is at the heart of obesity-related skin injury.6 Ulcers can occur within skin folds, where a catheter has burrowed into the skin surface, or over the hips bilaterally when the patient spends extended periods of time in a chair or wheelchair that is too narrow. Many obese patients demonstrate skin fold dermatitis, abrasions and/or cellulitis, excoriation from friction and shear, panniculitis, venous stasis ulcer, lymphedema, and perineal and genital skin erosion.6 Fungal and/or bacterial infections may be present in the axilla and below the breasts in both males and females.6 Often the size and depth of the wound(s) are profound, so the risks for a deep compartment infection are much higher. The clinician must evaluate the skin surface in such a way that skin changes leading to atypical pressure ulcers are identified in a timely manner.7 Frequent assessments must be done on these high-risk patients and appropriate equipment must be used to transfer patients safely and to redistribute pressure.

WOUND ASSESSMENT AND TREATMENT MODALITIES

A wound assessment must be completed by identifying the number of wounds and the staging of each wound, including description of size, pain, odor, and exudate. Wounds must be reassessed weekly to determine if the treatment is effective, and appropriate changes must be made to the treatment plan as required.1 If a wound is not healing or is producing excessive exudate after 2 to 4 weeks, a trial of topical antibiotics should be considered.1

Treatments must maintain the physiological integrity of the wound and should be managed according to the condition of the ulcer bed. The four steps of pressure ulcer management involve debridement, cleansing, prevention of infection, and selection of a dressing. The ideal dressing should protect the wound, be biocompatible, keep the wound moist, contain exudate, and minimize caregiver time usage.8

Select a wound cleanser solution (normal saline) and a mechanical means to deliver the solution to the wound. Cleanse the wound initially and with every dressing change, using minimal mechanical force. Avoid antiseptic solutions as they are cytotoxic.8 Eliminate dead space in the wound by loosely packing with appropriate dressing material. Packing too tightly may cause more damage to the ulcer by increasing the pressure on the wound bed tissue. Prevention of infection includes close monitoring of the dressings applied, prompt cleansing, and changing of the dressing. Picture-framing a dressing may be helpful when applying a dressing on any area that would be affected by movement or excessive moisture.

Wounds that contain dry or softened eschar or other hardened necrotic tissue will require a treatment that supports the debridement process. The process includes sharps debridement, mechanical debridement, enzymatic debridement, and autolytic debridement.1 Wounds with moderate to high exudate that are also necrotic may respond to both debridement treatment and an alginate product covered by an appropriate secondary dressing. Wounds with moderate to high amounts of exudate and/or in the debridement process should be assessed and changed daily.

Wounds that are in the inflammatory phase usually contain slough and have varying amounts of exudate. Choose a product that will absorb, cleanse, fill the dead space, protect the surrounding skin, and maintain a moist environment. Wounds that are in the healing phase and are granulating and/or epithelializing are generally pale pink to deep red in color, and the exudate volume will vary. Select a dressing that will provide protection for the healing wound and maintain a moist environment.1 Disturbing a healing wound bed too often will slow the healing processes and cause actual damage to the healing wound. Therefore, daily wound care may not be necessary.

The prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers require strategies supported by evidence-based practice that maintain standards, educate staff, and evaluate success.5 A structured and comprehensive program should include health care providers, patients, family members, and caregivers in the identification of at-risk patients and the teaching of prevention and treatment methods.

Bonnie George, RN, BSN, is a patient care manager, and Gail Malkenson, RN, BSN, CHPN, is a clinical educator at Hospice of the Comforter, Altamonte Springs, Fla. For additional information, contact .

REFERENCES

- O’Neil CK. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers. J of Pharm Prac. 2004;17:137-148.

- Reddy M, Gill SS, Rochon PA. Preventing pressure ulcers: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296:974-984.

- National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Pressure ulcer stages revised by NPUAP. Washington, DC; February 2007.

- Lyder CH. Pressure ulcer prevention and management. JAMA. 2003;289(2):223-226.

- Wurster J. What role can nurse leaders play in reducing the incidence of pressure sores? Nurs Econ. 2007:25(5):267-269.

- Gallagher S. Preplanning with protocol for skin and wound care in obese patients. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2004;17:442-443.

- Harley C. A clinical leader’s experience with bariatric wound care. Wound Care Canada, 2005;3:32-33.

- Bergstrom N, Bennett MA, Carlson CE, et al. Treatment of pressure ulcers. Clinical Practice Guideline. No 15. Rockville, Md: US Department of Health and Human Services; Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1994. AHCPR Publication No 95-0652.

ADDITIONAL READING

Camden SG, Shaver J, Cole K. Promoting the patient’s dignity and preventing caregiver injury while caring for a morbidly obese woman with skin tears and a pressure ulcer. Bariatric Nursing and Surgical Patient Care. 2007;2:77-82.

Courtney BA, Ruppman JB, Cooper HM. Save our skin: initiative cuts pressure ulcer incidence in half. Nurs Manage. 2006;37(4):35-46.

Department of Health and Human Services. Objective 1-16. Healthy People 2010. Washington, DC; 2000.

MacLean DS. Preventing and managing pressure sores. Caring for the Aged. 2003;4:34-37.

Madhuri R, Sudeep SG, Rochon PA. Preventing pressure ulcers: a systemic review. JAMA. 2006;296(8):974-984.

Salcido R. The AHCPR clinical practice guidelines, a decade later. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2002;15(2):52, 54.

Pressure sore illustrations courtesy of www.usc.edu/programs/pups/