By Julie K. Silver, MD

One recommendation from the IOM’s report was to create survivorship as a distinct phase of care that includes services and interventions to improve physical and emotional outcomes. Rehabilitation clearly has an important role in supporting the intended goals of this recommendation. Another recommendation was to provide a survivorship care plan to every patient that includes not only their past or current treatment, but also follow-up care, such as rehabilitation. The survivorship plan has garnered a great deal of attention among oncology health care professionals, including a new standard from the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer (CoC), which announced in 2012 that all of its approximately 1,500 accredited facilities are required to provide a plan to survivors by 2015. However, this new requirement is only as good as the services that are in place to treat patients’ cancer- and treatment-related problems. A plan without excellent, evidence-based oncology treatments, including rehabilitation, is not useful to survivors.

Another important factor behind the growing interest in cancer rehabilitation is that influential national and international organizations are now requiring this care for certification and/or accreditation. For example, the CoC lists cancer rehabilitation as an “Eligibility Requirement” (also referred to specifically as “E11”). The Joint Commission now has begun to offer a disease-specific care certification in oncology rehabilitation. And new cancer rehabilitation standards by the Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF) are pending publication. According to Chris MacDonell, Managing Director Medical Rehabilitation at CARF, “Cancer rehabilitation is a critical component of quality cancer care. The development of these standards will lead the way in the continuing recognition of cancer rehabilitation and its impact on those with cancer.”

Further fueling the aforementioned factors and driving the interest in cancer rehabilitation is a rapidly growing body of research that supports these interventions. In fact, according to a recent meta-analysis of cancer rehabilitation literature, oncology rehabilitation publications have grown 11.6 times while the whole field of disease rehabilitation has grown only 7.8 times.

Decreasing the Gap in Care

A new review titled “Impairment-Driven Cancer Rehabilitation: An Essential Component of Quality Care and Survivorship” demonstrated that while the majority of cancer survivors develop impairments that may be amenable to rehabilitation interventions, there is a significant gap in the delivery of these services. This review also highlighted the recent research about the relationship between physical and emotional sequelae due to cancer and its treatment, and noted that physical disability and reduced function are an important cause of distress and reduced quality of life in survivors.

Currently, there are nearly 14 million cancer survivors in the United States, and as stated earlier, the majority have or will develop physical problems and functional decline due to the disease or its treatment. The types of impairments patients develop can depend on many factors including the type of cancer, stage, and specific treatments. The way treatments are administered also may be a factor. For example, if the time period between chemotherapy treatments is shortened (“dose dense”) to try to improve efficacy in cancer treatment, this may result in less time for the body to recover from each treatment. Or, if chemotherapy and radiation treatment are given simultaneously versus sequentially, this might impact how an individual is able to physically recover afterward. Nora Fought, Oncology Program Supervisor at Lima Memorial Health System, Lima, Ohio, says, “Cancer rehabilitation is a critical part of the care continuum because expanding the multidisciplinary team to support cancer patients through their diagnosis and treatment is a piece of the survivorship puzzle that has been missing.”

CARF to Publish New Cancer Rehab Standards

A new set of standards for Cancer Rehabilitation Specialty Programs was developed in July 2013 and will be finalized and published in the 2014 Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF) Medical Rehabilitation Standards Manual. After intensive market research and interaction with stakeholders, CARF determined the need to move forward with the development of this critical set of standards. The recognition for Cancer Rehabilitation Specialty Programs across the continuum of care, including inpatient, outpatient, and community services, will enhance the services offered to those who have been diagnosed with cancer. The standards emphasize and focus on the need for organized, dedicated, cancer rehabilitation to be an integrated component of cancer care. CARF International worked to make this possible through interaction with a group of leaders in the field of cancer rehabilitation, consumers, and family members of individuals with cancer, researchers, and advocacy organizations. For more information about these standards, please contact Chris MacDonell at [email protected] or Dennis Stambaugh at [email protected].

—Julie K. Silver, MD

Integrating Cancer Rehabilitation into Survivorship Care

Immediately after diagnosis, the prehabilitation period may be an opportune time to provide assessments and interventions for physical problems. During this time, patients are often getting second or third opinions and waiting for surgical or other treatments to begin. Therefore, there is often a window of time in which to improve the physical and emotional health of the person. Pretreatment assessments are often done as part of cancer care, but coordinating these into evidence-based practice is an important consideration with newly diagnosed patients. Cancer prehabilitation may be defined as “a process on the continuum of care that occurs between the time of cancer diagnosis and the beginning of acute treatment, includes physical and psychological assessments that establish a baseline functional level, identifies impairments, and provides targeted interventions that improve a patient’s health to reduce the incidence and the severity of current and future impairments.” Adding prehabilitation to the care provides an opportunity to establish postdiagnosis, but pretreatment, baseline status, including identifying pretreatment impairments. The goals might include reducing treatment-related morbidity and/or mortality, decreasing hospital length of stay and/or readmissions, increasing available treatment options for patients who would not otherwise be candidates, and facilitating return to the highest level of function possible. In short, the primary goal of prehabilitation is to prevent or reduce the severity of anticipated treatment-related impairments that may cause significant disability.

As an example, consider a fairly typical man who has been diagnosed with head and neck cancer and undergoes surgery and chemoradiation. With this treatment, it is essentially guaranteed that he will develop multiple physical impairments with a reduced level of function and quality of life. Problems may include difficulty with swallowing and speech, malnutrition and weight loss, reduced cervical and shoulder range of motion, pain, fatigue, lymphedema, radiation fibrosis syndrome, and chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy.

Cancer prehabilitation with a speech-language pathologist may help to improve his swallowing and therefore his nutritional status during and after treatment. It is likely that he will stop driving during treatment, and he may not return to this without physical or occupational therapy to help him with cervical range of motion and other physical aspects of operating a motor vehicle safely. Complaints of fatigue may be improved by the physiatrist addressing sleep issues pharmacologically and/or the therapy team instructing him on sleep hygiene techniques. Physical therapy also may help provide a therapeutic exercise program that can improve symptoms of fatigue. If he has pain, this may be treated pharmacologically or through therapy interventions. The same is true if he develops radiation fibrosis syndrome and/or chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. New onset swelling in the affected region should be assessed by a physician to rule out cancer recurrence versus lymphedema or other sequelae. If lymphedema is the culprit, then a physical or occupational therapist trained in treating this condition should be involved. Nutrition, mood, and sexuality issues also should be addressed as appropriate by a multidisciplinary team that has expertise with this population.

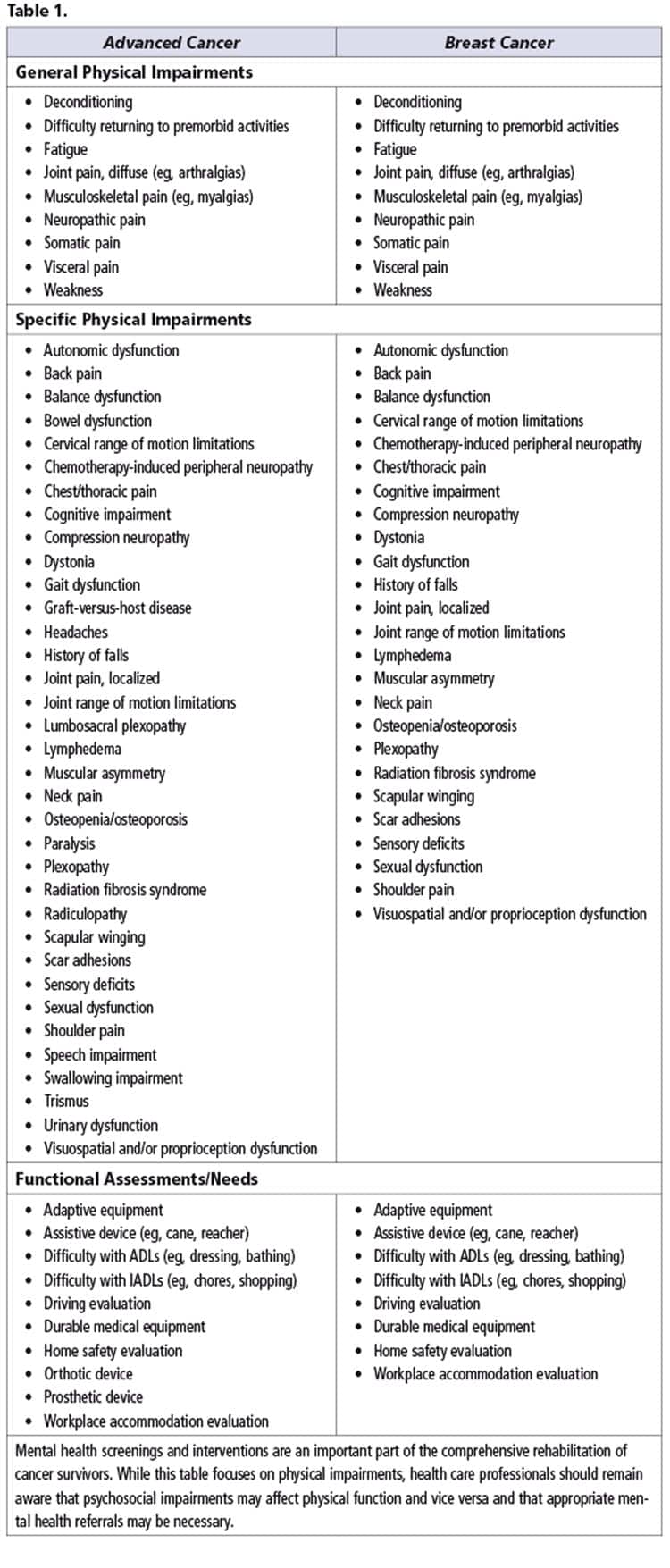

Rehabilitation teams are used to working together to assess and treat many impairments simultaneously. This is an example of how both cancer prehabilitation and rehabilitation can help survivors of all types of cancer—no matter what stage or when they were diagnosed—to function at a higher level and feel better. Table 1 (see at end of article) highlights some of the rehabilitation issues that may be prevalent in a breast cancer and/or advanced cancer population. There are more than 200 different types of cancer that affect more than 60 organs in the body. Therefore, the examples in this article are not meant to be inclusive of all cancers, but used as examples of rehabilitation opportunities that exist in this medically diverse and complicated population.

Developing Quality Cancer Rehabilitation Services

Developing quality rehabilitation services that become an integrated part of cancer care is crucial, and begins with training oncology and rehabilitation health care professionals in evidence-based care. In the oncology department, clinicians must train to appropriately screen patients for impairments. Dual screening for physical and psychological impairments is ideal so survivors are referred for the help they need. Screening systems should be put in place so this becomes a standard part of cancer care, rather than having the patients “self-identify” when problems arise. A standardized screening process will help to support reimbursement as well. For example, with Medicare’s therapy caps, screening patients to identify impairments early, before they have progressed, means less treatment will be necessary. This new “standard of care” means more survivors will be referred for rehabilitation services but will need to be seen for fewer visits to accommodate third-party payor caps. Therefore, it makes sense to screen all survivors for physical impairments, identify these early before they have progressed, and treat them quickly and effectively.

Once the clinicians are trained and there is a standardized screening process in place, then referral sources need to be educated about the cancer rehabilitation services available. This includes oncologists, primary care physicians, mental health professionals, and others. This also includes survivors, who need to understand why they are being referred for more medical appointments. Because there is a strong business case for cancer rehabilitation and offering better care, there is often a “quality initiative” in hospitals, and the administration can play an important role in supporting the success of a cancer rehabilitation service line. Stephanie Dotson, a physical therapist and the Rehabilitation Services Manager at OSF St. Joseph Medical Center, Bloomington, Ill, says, “When it comes to cancer rehabilitation, our administration is extremely engaged. The word ‘cancer’ causes people to stop and read or listen. Our administration has been extremely supportive in helping us spread the word about cancer rehabilitation and helping us to make connections with physicians.”

CARF International accreditations focus on the “persons served,” who, of course, are the survivors. And, at the end of the day, offering quality cancer rehabilitation services means that survivors have better care and better lives. Caryl Perdaems, an occupational therapist and manager of the Wound and Lymphedema Clinic at Bozeman Deaconess Hospital, Bozeman, Mont, sums it up nicely when she explains that offering a high-quality cancer rehabilitation program “shows our patients that we care not only about their disease process, but about their wellness!” RM

Julie K. Silver, MD, is an associate professor in the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at Harvard Medical School. She developed the STAR Program (Survivorship Training and Rehabilitation) Certification, which has been adopted by more than 100 hospitals, cancer centers, and independent physical therapy and oncology practices in the United States (www.OncologyRehabPartners.com). Dr Silver recently served on a committee to help develop the new CARF cancer rehabilitation specialty standards. For more information, contact [email protected]