The researchers add that the active thrombin correlates with disease severity. Gladstone Institutes notes in a recent news release that previously, Akassoglou and her team discovered that a key step in the progression of MS is the disruption of the blood brain barrier (BBB). Once fibrinogen seeps into the brain following a breakdown of the BBB, thrombin converts fibrinogen into fibrin. The researchers explain that as fibrin builds in the brain, it causes an immune response that paves the way to degradation of the nerve cells’ myelin sheath, contributing to the progression of MS.

As the researchers already knew about the progressive buildup of fibrin early in the development of MS in both human patients and animal models, “we wondered whether thrombin activity could serve as an early marker of disease. In fact, we were able to detect thrombin activity even in our animal models—before they exhibited any of the disease’s neurological signs.”

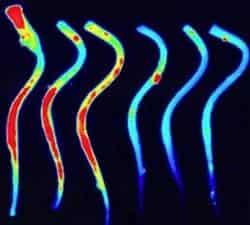

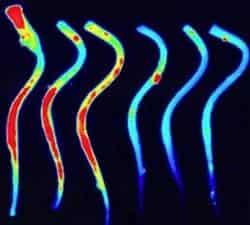

To obtain these findings, the release reports that during laboratory experiments on mice modified to mimic the signs of MS, they used an Activatable Cell-Penetrating Peptide (ACPP). The thrombin-specific ACPP was developed to track thrombin activity in mice as the disease progressed. The team detected heightened thrombin activity at specific disease “hot spots,” or regions where neuronal damage developed over time, says Dimitrios Davalos, PhD, associate director of the CIVIR and one of the paper’s lead authors, Gladstone Staff Research Scientist.

“…When we compared those results to those of a separate, healthy control group of mice, saw that thrombin activity in the control group was wholly absent,” Dimitrios adds.

Kim Baeten, PhD, lead author, states that the result reinforce the, “principle that a thrombin-specific molecular probe could be used as an early-detection method.”

The team also emphasizes that the findings provide insight into the underlying molecular processes that facilitate the progression of MS and may pave the way for the development a thrombin-specific ACPP to allow for early patient diagnosis and therapeutic intervention.

Photo Caption: Using advanced detection and imaging techniques, Gladstone scientists were able to track thrombin activity in mice modified to mimic MS (left) compared to healthy controls.

Photo Credit: Dimitrios Davalos, Kim Baeten, Katerina Akassoglou

Source: Gladstone Institutes