According to a news release from the NIH/NINDS, the study suggests a similar response may occur in patients with mild head injury. The researchers also report that certain molecules applied directly to the mouse skull can bypass the brain’s protective barriers and enter the brain.

McGavern explains that in the mice, the researchers observed leakage from blood vessels underneath the skull bone at the site of the injury, “similar to the type of effect we saw in almost half of our patients who had mild traumatic brain injury. We are using this mouse model to look at meningeal trauma and how that spreads more deeply into the brain over time,” McGavern says.

The release notes that researchers also found that the intact skull bone was porous enough to allow small molecules to get through to the brain. Smaller molecules reportedly reached the brain faster and to a greater extent than larger molecules.

The researchers state applying glutathione directly to the skull surface post-brain injury reduced the amount of cell death by 67%. The concept of having a time window to accomplish this, “potentially up to 3 hours, is exciting and may be clinically important,” McGavern points out.

Researchers add they also used a microscopic technique to film what occurred just beneath the skull surface within 5 minutes of injury. The researchers also observed cell death in the meninges and at the glial limitans. The release notes that cell death in the underlying brain tissue did not occur until 9 to 12 hours post-injury. Once glial limitans break down and develop holes immediately after injury, researchers say, microglia move up to the brain surface, filling the holes.

McGavern notes that microglia accomplish this in two ways, “If the astrocytes, the cells that make up the glial limitans, are still there, microglia will come up to ‘caulk’ the barrier and plug up gaps between individual astrocytes. If an astrocyte dies, that results in a larger space in the glial limitans, so the microglia will change shape, expand into a fat jellyfish-like structure and try to plug up that hole. These reactions, which have never been seen before in living brains, help secure the barrier and prevent toxic substances from getting into the brain.”

The study results suggest that contrary to previous studies’ findings; inflammatory response in a mild traumatic brain injury model may be beneficial during the first 9 to 12 hours post-injury.

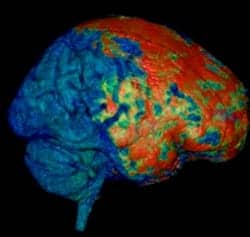

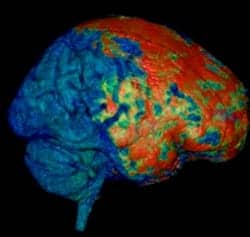

Photo Caption: This 3D MRI of a human brain reveals injury (in red) to the brain’s coverings following mild head trauma.

Photo Credit: Image courtesy of Lawrence Latour, Ph.D., National Institutes of Health and the Center for Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine.

Source: NIH/NINDS