|

| Losing weight helps bariatric clients lower their risk of developing osteoarthritis and musculoskeletal problems, while at the same time decreasing pain-related disabilities and working on cardiovascular endurance. |

Obesity has been described as a “worldwide epidemic” by the World Health Organization, while here in the United States it has become a substantial medical and social problem. It has been estimated that between 30% and 54.9% of the adult population are considered obese, resulting in an estimated 100,000 to 280,000 deaths per year due to complications associated with this condition. The cost required to treat obesity is also staggering; it accounts for almost 10% of the national health care costs, more than $99 billion a year.

The purpose of this article is to explore the musculoskeletal impact of treating the outpatient obese or bariatric population, and to understand the complicating comorbidity, psychological, and physical plant factors that influence their care.

The World Health Organization defines obesity as anyone having a body mass index (BMI) greater than 30, and severely obese as BMI greater than 40. BMI is calculated by dividing the patient’s weight (kg) by their height (m2). According to Ashford and St Peter’s Hospitals National Health Service, United Kingdom, a bariatric patient will be defined as “anyone, regardless of age, who has limitations in health and social care due to their weight, physical size, shape, width, health, mobility, tissue viability, and environmental access with one or more of the following … : Has a BMI >40 kg/m2 and/or is 40 kg above ideal weight for height; Exceeds the working load limit and dimensions of the support surface such as a bed, chair, wheelchair, couch, table, toilet, or mattress.” For simplicity, in this paper, the term “obesity” will be used for both these distinct populations.

The musculoskeletal effects of obesity are well documented. Hip, knee, and low back osteoarthritis (OA) pain is a common complaint, and causes a “higher work restricting pain than the general population.” Obesity has been found to cause a fourfold higher prevalence of OA in weight-bearing joints.

Obesity puts extra force on bones and joints. Consequently, obesity increases the risk of developing osteoarthritis and the need for joint replacement. In the past, joint replacement was not even an option for obese patients, especially very obese patients. In recent years, joint replacement surgery has become feasible for heavier osteoarthritis patients.

Looking for bariatrics equipment? Check out Rehab Management’s 2010 Buyer’s Guide.

Medical professionals who treat orthopedic patients may find an increasing number of people seeking care for the conditions as noted above, as well as for management of the associated pain. A 2007 study by Janke, Collins, and Kosak suggests a direct link between pain and obesity where patients, just by losing weight, decreased their pain level by a hypothesized link to mechanical, structural, behavioral, and metabolic mechanisms. (Other studies suggest that losing weight lowers the risk of developing OA and musculoskeletal problems, and decreasing pain-related disabilities.)

As the number of obese individuals increases, there is a greater possibility of medical professionals treating nonoperative, surgical, and postoperative patients. Research has indicated that obesity is “associated with a premature requirement for hip and knee surgery” occurring 10 to 13 years sooner than in those of an average weight. When treating individuals presenting with these conditions, the role of the treating professional must include the appropriate referrals for counseling, education in weight management (if possible), exercise guidance, and nonoperative and postsurgical medical management.

|

| Examination/treatment room tables and chairs should be structurally sound to accommodate bariatric patients. |

| Examination/treatment room tables and chairs should be structurally sound to accommodate bariatric patients. |

|

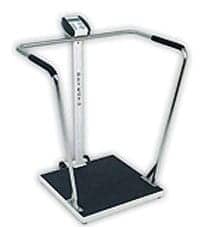

| Scales with an extrawide platform and sturdy handrails are ideal for weighing bariatric patients. |

In addition to the musculoskeletal impact of obesity, the therapist will see such secondary medical issues in these patients as sleep apnea, obstructive lung disease, renal dysfunction, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, thrombosis, altered drug interactions, as well as coronary artery disease, stroke, peripheral neuropathy, higher incidences of bone fractures, dermatitis, skin ulcers, stress incontinence, and emotional disturbances. Combining the musculoskeletal issues with any of the above comorbid medical conditions may lead to a longer rehabilitation process, often with less than ideal results.

In addition, the obese patient may present with significant psychological and mood deficits that can impact any rehabilitation being rendered. Nancy M. Petry, PhD, and fellow researchers have found through extensive analysis “an association between body weight and psychiatric conditions. The obese and extremely obese have higher increased odds of mood and personality disorders including major depression, manic episodes, and antisocial, avoidant, schizoid, paranoid, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders compared to the normal weight individuals.” Tahany Gadalla, PhD, states: “It is unclear whether obesity causes depression or depression causes obesity.” Clearly, the health professional treating the obese patient must keep this in mind, especially those who do not have the psychiatric background to deal with the individual exhibiting any of the above signs. The treating professional must have available referral resources to make sure the obese patient has adequate care.

Besides being prepared to treat the medical effects of obesity, health care providers must consider the physical surroundings of the clinic. Waiting room furnishings, restroom accommodations, and office equipment should be structurally sound for use by these individuals. (An online and catalog review of the average weight capacities of office equipment and furniture reveals the average step stool’s weight limit is 250 pounds, examination tables 300 to 400 pounds, exercise equipment—including treadmills, recumbent bikes, etc—from 250 to 300 pounds, wheelchairs up to 300 pounds, and floor-mounted toilets 250 pounds.) Having equipment that will accommodate a weight capacity of 500 pounds should allow for care of the majority of the obese population. This includes waiting room chairs and examination/treatment room chairs and tables. Common items in the rehabilitation process such as treadmills, stationary bikes, recumbent bikes, and therapy balls also need to be properly weight rated. Additional appointments should be considered essentials for the patient’s safety and modesty needs; among these are widened doorways and hallways, bathroom railings, blood pressure cuffs, safety equipment, and patient gowns sized to handle the larger individual. Although many obese individuals coming into the outpatient clinic arrive either under their own power, or via medical transportation or commercial ambulance, having heavy-duty lift equipment is a plus. If you are unable to provide necessary changes or equipment, then having the ability to refer out to a clinic that is able to accommodate the obese patient is important.

Treating the obese or bariatric patient is more complicated than first appears. For the outpatient professional who specifically caters to the obese patient, the material presented in this article comes as no surprise. Those with more limited exposure treating this group need to be aware so they are better prepared to tackle this growing population. Orthopedically, they typically present with pain and limitations in the weight-bearing joints of the lower extremities, and may require medical procedures sooner than the average population. The obese population present with a possible host of secondary medical issues, as well as psychiatric and mood disorders that complicate their rehabilitation recovery. They require the treating professional to be knowledgeable in the special conditions unique to this patient group, both physical and psychological, and require the use of specialized equipment and furniture. Even with this worldwide epidemic, the health care professional in this country is an important part of the equation by providing treatment, education, and guidance and acting as a active referral source so the obese individual can be afforded the same health care as any other person seeking medical treatment.

Timothy J. Bayruns, DPT, OCS, CSCS, is a physical therapist with 26 years of clinic experience treating in a wide variety of settings. He is currently working in an outpatient orthopedic facility as a musculoskeletal team leader for Good Shepherd Penn Partners, Philadelphia. For more information, go to www.goodshepherdrehab.org.

Safe Lifting Techniques

Proper lifting technique has long been a given for physical therapists when lifting bariatric patients—aiming to shield their own backs from injury—but many therapists also rely on equipment when exertion is needed for this task. Some say that proper lifting alone is not enough. Many therapists agree that to help avoid injury and liability when performing this type of task, which can entail moderate and maximum assist, it may be prudent to use a mechanical lift or manual techniques along with devices such as transfer sheets.

Through the years, many therapists were schooled to drag patients out of bed using a slide, a transfer board, or a draw sheet with the assistance of a lift team that may comprise a half dozen assistants. The American Physical Therapy Association, Alexandria, Va, has taken steps to update patient-handling methods and guard the workplace well-being of the therapists themselves.

Many hospitals and trauma centers are equipped with portable or permanently mounted ceiling lifts, which may accommodate patients who weigh up to 600 to 800 pounds. Ceiling lifts may feature a walking sling. Some therapists place a turning sling beneath the patient and rely on the ceiling lift for repositioning the individual. A floor lift or a Hoyer-type lift with a repositioning sling may prove useful if the ceiling lift is not present.

A system that suits the needs of bariatric patients and therapists alike could include the following components: a weight-rated bed; a lift; and a target surface, which could be a wheelchair, bedside commode, or stretcher chair. These tools can assist patients throughout their treatment—from the emergency department, to the intensive care unit, to acute care, subacute care, transitional care, the nursing home, and on to home care. This equipment combination may help avoid a failure that can ensue with bariatric suites, ie, a lack of portability that results in the patient becoming stranded.

Many manufacturers have also enhanced their offerings to include specialty beds, which may expand to 50 inches, bariatric wheelchairs and wheelchair cushions, bedside commode chairs, bariatric shower/commode chairs, bariatric walkers, motorized stretchers, and air-inflated patient-transfer products.

While many facilities are gravitating toward a heavier reliance on lifting technology, much physical effort is still involved. Specialized training may be offered so personnel learn the most effective and safe methods for moving and handling patients. These individuals help patients in and out of bed and aid with turning, and they may be especially active in mobilizing bariatric patients. Often, two-person teams assist with the care of bariatric patients as soon as they arrive—which entails maneuvering patients out of the ambulance and can pose a challenge even with the aid of equipment. Lift teams may enhance the therapist’s sense of security when dealing with bariatric patients.

Whether implementing lift teams or special equipment, budget concerns often play a role in the decision. A proactive approach from administrative decision-makers may help save money in the long term, especially if equipment can help health care workers to avoid injuries during patient care. Smaller facilities such as outpatient rehabilitation centers may have only two therapists, so there is a good likelihood that assistive equipment would be needed. Larger institutions would likely find it easier to assemble a team.

Bariatric Wheelchair Options

Therapists may encourage bariatric clients to consider powered mobility even if they are sure they want a manual wheelchair, and to compare the two options. Newer power chairs with the electronic mechanism stowed beneath the seat allow a larger seat to be placed on top. The narrower overall profile allows clients to adjust the width and depth, and remove backrests, and a tilt-in-space position may prove beneficial for clients with strong endurance for dynamic activity. Air-inflated tires have been replaced on many bariatric wheelchairs with solid urethane and a variety of other durable materials.

Some bariatric wheelchairs sport handles that measure almost 3 feet across, which can make it difficult for small caregivers to push the chair. Responsive manufacturers have devised narrower bars. Over time, more bariatric wheelchairs are being motorized—as are transport beds, which spotlight the needs of health care workers alongside the needs of their patients.

Resources

Anandacoomarasamy A, Caterson I. The impact of obesity on the musculoskeletal system. Int J Obes. 2008;32:211-222.

Anandacoomarasamy A, Fransen M, March L. Obesity and the musculoskeletal system. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009;21(1):71-77.

Anderson JJ, Felson DT. Factors associated with osteoarthritis of the knee in the first national Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (HANES I). Am J Epidemiol. 1988;128(1):179-89.

Barr J, Cunneen J. Understanding the bariatric client and providing a safe hospital environment. Clin Nurse Spec. 2001;15(5):219-223.

Chan G, Chen C. Musculoskeletal effects of obesity. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21(1):65-70.

Colditz GA. Economic costs of obesity and inactivity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31:S663-S667.

2009 Therapy Product Catalog. Clear Lake, SD: Empi Therapy Solutions.

Felson DT, Zhang Y, Anthony JM, Naimark A, Anderson JJ. Weight loss reduces the risk for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in women. The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116(7):535-539.

Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson DF, et al. Excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA. 2005;293:1861-1867.

Gadalla TM. Association of obesity with mood and anxiety disorders in the adult general population. Chronic Dis Canada. 2009;30(1):29-36.

Gibson GTJ. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: underestimated and undertreated. Br Med Bull. 2004;72:49-64.

Huang MH, Chen CH. The effects of weight reduction on the rehabilitation of patients with knee osteoarthritis and obesity. Arthritis Care Res. 2000;13(6):398-405.

Huseman S. Preparing for a bariatric center of excellence site survey. J Nurses Staff Devel. 2009;25(11):2-10.

Janke EA, Collins A, Kozak AT. Overview of the relationship between pain and obesity: What do we know? Where do we go next? J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44(2):245-262.

Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systemic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psych. 2010;67(3):220-229.

McGlinch BA, Que FG, Nelson JL, Wrobleski DM, Grant JE, Collazo-Clevell ML. Perioperative care of patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(10 suppl):S25-33.

Misscio G, Guastamacchis G, Brunani A, Priano L, Baudo S, Mauro A. Obesity and peripheral neuropathy risk: a dangerous liaison. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2005;10(4):354-358.

Muir M, Archer-Heese G. Essentials of a bariatric patient handling program. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. 2009;14(1):1.

Muir M, Haney L. Designing space for the bariatric resident. Nursing Homes/Long-term Care Management. 2004;53(11):25-28.

National Institutes of Health and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Obesity Educational Initiative. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Education, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. Bethesda, Md: NIH; June 1998.

Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. In: Report of a WHO Consultation. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2000.

Pelosi P, Croci M, Ravagnan I, Vicardi P, Gattinoni L. Total respiratory system, lung, and chest wall mechanics in sedated-paralyzed postoperative morbidly obese patients. Chest. 1996;109:144-151.

Peltonen M, Lindroos AK, Torgerson JS. Musculoskeletal pain in the obese: a comparison with a general population and long-term changes after conventional and surgical obesity treatment. Pain. 2003;109(3):549-557.

Petry NM, Barry D, Pietrzak RH, Wagner JA. Overweight and obesity are associated with psychiatric disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:288-297.

Pieracci FM, Barie PS, Pomp A. Critical care of the bariatric patient. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(6):1796-1804.

Professional Rehab Catalog 2010. Bolingbrook, Ill: Sammons Preston.

Stallings SP, Kasdan ML, Soergel TM, Corwin HM. A case-control study of obesity as a risk factor for carpal tunnel syndrome in a population of 600 patients presenting for independent medical examination. J Hand Surg. 1997;22(2):211-215.

Stunkard AJ, Stinnett JL, Smoller JW. Psychological and social aspects for the surgical treatment of obesity. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:417-429.

The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Decrease Overweight and Obesity. Rockville, Md: Public Health Service, Office of Surgeon General; 2001.

Tizer K. Extremely obese patients in the healthcare setting: patient and staff safety. J Ambul Care Manage. 2007;30(2):134-141.

World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. WHO/Nut/NCD/98. June 1, 1997.