The warning signs are subtle—a twinge of discomfort, a small red spot on the skin—but left untreated, pressure sores can lead to infection, osteomyelitis, and even death. Unfortunately, chronic pressure sores affect millions of Americans, with between 1.5 million and 1.8 million new cases occurring every year.1 While there are ways to heal pressure sores when they are caught early enough, the best medicine is prevention, and PTs play a vital role in helping clients learn how to recognize and avoid skin breakdown.

Pressure sores are very common among seniors, who are more likely to maintain the same seated or reclined position for long, uninterrupted periods. The most susceptible clients are those without protective sensation, such as patients with spinal cord injuries. “If you have sensation, then you know you have a sore very early on,” says Lauren Rosen, PT, MPT, APT, of St Joseph’s Children’s Hospital of Tampa, Fla. “If you don’t have sensation, then you have to actually, actively seek out the sore. But in a lot of the populations, they are really not good at finding them until there’s a significant sore.”

For all patients, vigilance is key, and seating and positioning specialists are uniquely suited to helping clients take the steps they need to avoid pressure sores. In addition to showing clients how to perform regular pressure lifts and skin checks, these therapists make sure that the seating system itself is right for the client’s individual needs.

PREVENTIVE MEASURES

Client education about pressure sores begins when they are inpatients, and they learn to incorporate good habits into their daily routines. “We can design the best cushions and the best seating systems in the world, but if you are always sitting in the same position, chances are high that your skin is going to break down,” Rosen says.

PTs particularly stress the importance of pressure relief, which means performing a lift or position change for up to several minutes each hour to allow oxygen profusion in weight-bearing areas. “Patients who have good upper-extremity strength can do pressure relief by lifting themselves up and shifting their position,” Rosen says. “Patients who don’t will usually have either a manual tilt-in-space system or a power tilt-in-space system.”

The general consensus has been that clients should perform a lift or a tilt-in-space for at least 1 minute each hour. But Jan Furumasu, PT, APT, of the Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center, Downey, Calif, notes that this may not be enough for every patient. “A lot of times, it takes longer; it can take up to 5 minutes,” she says. “It depends on the person. It depends on how they sit, on their body type, and what their skin is like.”

Clients and their caregivers also learn to be meticulous about daily skin checks. They look for obvious sores or red spots and also check for areas of the skin that don’t blanch, as this can be an early warning sign. “For patients who are functional, in a lot of cases, they use long-handled mirrors to see the parts of their body that they can’t contort themselves to see,” Rosen says.

Both of these routines are effective measures to catch pressure sores in the early stages. “Usually, you first see a pressure sore as a red spot on your skin,” Rosen says. “If you catch it there, it’s a lot easier to heal it than once it has broken through the skin.”

Of course, there is no perfect formula for avoiding pressure sores altogether. “We teach [clients] about skin care and wound management, but sometimes despite that, they still have skin breakdown for various reasons,” Furumasu says. “It could be transfers. It could be sitting at work or in school for long hours and not being able to do pressure raises.” She adds that losing weight rapidly due to the flu or pneumonia could also expose bony prominences that were not an issue before.

There are several ways to treat open sores, and wound care centers can provide clients with medications, ointments, and even drains, when necessary. Flap surgery is usually a last resort. “Unfortunately, when you get to that point, it’s not overly successful,” Rosen says.

When sores do occur, the most effective way to heal them is by staying off of them completely. This could mean weeks of bed rest, a prospect that might be difficult for patients with work or school obligations, but it is a necessary step to ensure recovery. “Once their skin is open, then it doesn’t matter if they’re on a good pressure-relieving cushion,” Furumasu says. “If the sore’s not healing, it’s because their body weight, just from sitting, is tearing all of that brand-new tissue, or it could be the heat and moisture accumulation when they sit. Once their skin is open, the only way to heal it is to stay off of it.”

CLUES FOR CARE

Once pressure issues are detected and the wound has been healed, PTs work with clients to pinpoint the cause to ensure that it doesn’t happen again. Sitting in the same position for too long puts pressure on bony prominences, which can damage the skin over time. But while the seating system is often the first suspect, it is not always the culprit. There are several contributing factors to consider when assessing the cause of a pressure sore, which means therapists need to do some detective work. This involves using a combination of diagnostic tools, such as pressure-mapping systems, as well as asking the right questions.

Furumasu recently worked with a client who presented with a pressure sore on the sacrum. The referring nurse practitioner thought the sore might be related to the patient’s seating system. But by conducting pressure mapping and working with the client to find out the different positions that could have caused the sore, Furumasu discovered that the sore was likely caused by sitting up in bed, not by the seating system.

“We always want to try to problem-solve where they got [the pressure sore] from,” Furumasu says. “Was it sitting? Was it driving in their car for too many hours without sitting on a cushion?” She adds that sheering can be a major factor, and that patients may develop sores during transfers or from accidental errors, such as a caregiver placing the cushion backward in the wheelchair.

Often, a pressure sore is a result of multiple causes, and moisture buildup is a common factor, particularly for clients in humid climates, such as Florida. Perspiration can build up next to the skin and cause breakdown. Rosen encourages clients in these areas to stay in the air-conditioning as much as possible and says that cushions with moisture control can also be effective.

Another issue is incontinence. “One of the biggest things that I talk to families about is toileting properly, putting somebody on a good schedule,” she says. “All of these things are really important to keeping somebody healthy.”

FINDING THE RIGHT FIT

A seating system tailored to a client’s individual needs can go a long way toward preventing pressure sores. Furumasu recently worked with a client who presented with a pressure area on her coccyx that resulted in surgery. The patient, who has had a spinal injury for more than 30 years, had received a new chair from her HMO, and Furumasu determined that the chair was too big for her. “Because the back was too high, she couldn’t sit back,” Furumasu says. “She kept sliding and sliding.”

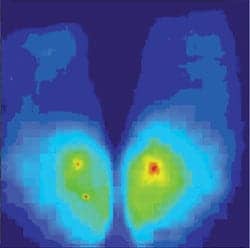

Seating and mobility clinics often use pressure-mapping systems to help detect areas that could be at risk for developing pressure sores. It shows where pressure is being exerted and whether a client is weight-bearing evenly. This, in turn, helps PTs choose the right cushion and seating system to support the client. However, Furumasu cautions that recommendations cannot be based on pressure mapping alone. “You really have to be able to physically palpate their bony prominences,” she says. “You can get a false negative on a pressure-mapping display unless you really understand what you’re looking at.”

In addition to incorporating pressure-mapping systems into the evaluation process, seating specialists often use the systems for client education. “Sometimes [clients] think they’re doing a pressure relief and they’re really not, so we’ll use it kind of as a biofeedback technique,” Rosen says. “We’ll show them how far they have to go forward or to the side in order to get the weight off of the spots where they’re at risk.”

It’s also a good opportunity to reinforce the importance of pressure lifts. “As we’re picking a seating device, we’re also educating the entire time about the importance of doing pressure relief, whether it’s the client or the caregiver doing it,” she says. “We really try to drill that into them as a preventative measure.”

When it comes to seating, finding the right cushion is key. A variety of support surfaces, such as foam, air, and gel, are available to accommodate clients with different needs. There are even special cushions for patients with pelvic obliquities. Therapists have to weigh many factors when choosing a cushion for patients—a cushion that works beautifully for one client may be the wrong fit for another.

“If a person has a hard time transferring off of an air cushion, then they may need to try a different type of pressure-relieving cushion,” Furumasu says. “It’s good to have the therapist’s functional perspective and not just look at the quality of the cushion itself. You have to understand what the person’s functional capabilities are.”

Because placing clients in the right seating system is so important, having a seating specialist do a proper evaluation is essential. Changing a system is never as easy as switching out a cushion. “If you change somebody’s seating, it always affects how they push the chair,” Furumasu says. “If they’re in a manual, lightweight chair, it affects how they transfer. Some people can’t sit on a higher cushion because of how they transfer. So, there’s a lot of basic science that goes into measuring different factors.”

Of course, cushions are only one aspect of a seating system. Footrests that are too long may not support the legs properly and cause sores to form. Footrests that are too high do not support the thigh, which could shift the weight to the sacrum or the ischial tuberosities. Even properly positioned armrests make a difference. “The seating system as a whole, the way the client is seated, is very important,” Rosen says. “The cushion is obviously the first place to look, but it’s certainly not the only place that we look, especially if somebody starts to have skin breakdown. It could be a lot of factors on the chair that are causing it.”

Consulting with a seating specialist helps avoid problems that could develop because of a well-meaning but improper fit recommended by an equipment dealer, or even another therapist. “It is important that a therapist knows their limits,” Rosen says. “If there is a complicated patient and a therapist doesn’t know a lot about seating and positioning, they should refer to a seating and positioning specialist.”

Ann H. Carlson is a contributing writer for Rehab Management. For more information, contact .

REFERENCE

- Beitz JM. Wound, ostomy, continence nursing: A career for the new millennium. Nursing Spectrum. Available at: nsweb.nursingspectrum.com/cfforms/GuestLecture/woundcare.cfm. Accessed August 2, 2007.