For more than a century, scientists have known that while the commands that initiate movement come from the brain, the neurons that control locomotion once movement is underway reside within the spinal cord.

In a study published recently in the journal Cell, researchers report that, in mice, they have identified one particular type of neuron that is both necessary and sufficient for regulating this type of movement. These neurons are called ventral spinocerebellar tract neurons (VSCTs).

“We hope that our findings will open up new avenues toward understanding how complex behaviors like locomotion come about and give us new insight into the mechanisms and biological principles that control this essential behavior. It’s also possible that our findings will lead to new ideas for therapeutic avenues, whether they involve treatments for spinal cord injury or neurodegenerative diseases that affect movement and motor control.”

— the paper’s senior author George Mentis, associate professor of pathology and cell biology in the Department of Neurology at Columbia University

VSCTs were discovered in the 1940s, but researchers have long believed that their main function was to relay messages about neuronal activity from the spinal cord to the cerebellum. The new study reports that instead they control locomotor behavior both during development and in adulthood.

“These findings were a huge surprise,” Mentis says. “One of the key discoveries in our study was that apart from their connection to the cerebellum, these neurons make connections with other spinal neurons that are also involved in locomotor behavior via their axon collaterals.”

Several Approaches

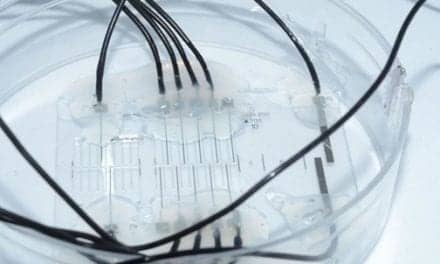

The research involved several novel experimental approaches. One part of the research used optogenetics, employing LED light to regulate certain proteins that were expressed selectively in VSCTs to either activate or suppress the neuronal activity. Another set of experiments used chemogenetics, a process by which a chemical compound is used to activate or suppress synthetic ligands expressed artificially in these neurons, controlling their activity.

Leveraging the ability of intact spinal cords from newborn mice to function in a dish, the researchers showed that activation of VSCTs by light induced locomotor behavior. When VSCT activity was suppressed by light or by drugs, ongoing locomotor behavior was halted. During adulthood, freely moving mice stopped moving when the activity of VSCT was suppressed by injecting an inhibitory drug.

Locomotor behavior was also tested by the ability of mice to swim. Mice were unable to swim and simply floated in the water when VSCTs were silenced. In all of these models and experiments, the researchers demonstrated that VSCTs alone were both necessary and sufficient for controlling locomotor activity — activating them was enough to induce activity while suppressing them was enough to stop it.

Limitations to Mice Studies

Mentis acknowledges that there are limitations to conducting this type of research in mice, including the fact that while humans are bipedal, mice are quadrupedal; thus, their locomotion could be regulated in a different way. But he notes that other research on neurodegenerative diseases and processes in mice has led to clinical trials in human patients, suggesting that these findings are also likely to be applicable.

For their next steps, the team plans to identify and map precisely the neuronal circuits that VSCTs make with motor neurons and other spinal neurons. They also would like to identify select genetic markers and uncover potential subpopulations of VSCTs and explore their role in different modes of locomotion. Finally, they plan to explore how the function of VSCTs is altered in the context of pathology and neurodegenerative diseases.

[Source(s): Cell Press, Science Daily]