When asked to write about a “hot” topic related to today’s wheelchair and seating practices, one might assume leading topics would include: recent changes in Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) policies; introduction of competitive bidding for suppliers to provide wheelchairs in various regions across the country; reduction of US manufacturers’ product lines eliminating some of their best chairs, etc. However, despite these very challenging, very frustrating, and at times disheartening changes, we believe that a skillful client-centered team evaluation, with AT-expert members consisting of physiatrist, therapist, rehabilitation engineers, rehabilitation counselor, certified suppliers, the client (end user), and the client’s family or caregiver, supported by careful and compliant documentation, can still have a realistic chance to secure funding for appropriate equipment for end users. However, the success of the evaluation process cannot stop with the approval of funding, placement of order, or final delivery of the device by the supplier to the home. This would ignore the importance of the final fitting and training by members of the clinical team to ensure the original recommendations truly meet the end user’s mobility and seating needs, in addition to ensuring that the final training and instructions will allow the user to safely operate and use the functions of the chair effectively and safely. The more complex the technology, the more involved and time-consuming the training. However, failure to invest in the time and quality of training will cause inappropriate use of the technology, which may cause harm and injuries that provide third-party payors added reason to cut funding for existing technology.

Yet how do clinicians find time for extensive training? How do we know that the education and training are followed through? And how, for example, are power seat functions (PSFs) actually utilized by the end users? These questions and clinical concerns led to the development of a “virtual coach,” which is a tailored reminder that guides the end user in the appropriate use of PSFs.

Power seat functions that include tilt/recline/elevating legrests/seat elevator are “dynamic” seat functions that should be recommended to end users who are “static” sitters. The term “static sitter” means that through progressive decline of their physical capabilities, the person is no longer able to transfer independently or conduct independent weight shifts for effective pressure relief to reduce the risk of pressure sores, spasticity, edema, orthostatic hypotension, and chronic pain. Our clinical experience, however, has shown that some of our power wheelchair users who have been provided these PSFs return to our clinic for problems such as fatigue, pain, or pressure sores that should have been addressed or prevented with appropriate use of PSFs. Although clinicians educate end users about the proper use of the functions, ie, emphasizing the importance of using “tilt” first, then recline followed by elevating the legrest, during the final fitting and training sessions, they find that with more involved users, they simply run out of time because the amount of information is too much and sometimes too overwhelming to be taken in at one visit. There are also end users who, during the final fitting and training visit, express and demonstrate understanding in how to operate their power wheelchair and seat functions. These users understand the benefits of using these functions as they are experiencing the effects of positioning changes, yet they simply forget to use these functions or forget how to operate them once they return home.

These clinical concerns and experiences were confirmed by previous research survey studies that show most PSF users utilize these functions for comfort rather than specific medical reasons for which they have been recommended and justified for funding.1 Another research study tracked actual PSF use with 11 power wheelchair users by adding instrumentation with sensors and data loggers to their chairs, which collected data for a 2-week period. Analysis of the data revealed that they did not use the functions as clinicians would have expected, as they did not adjust seating positions frequently and seldom used large tilt angles (greater than 30°) that correspond to effective weight shifts and pressure relief in previous laboratory studies.2 The data revealed a problem given the fact that a full complement of PSFs can easily double the cost of a wheelchair and its provisions have to be medically justified to secure funding. Yet many users are not using the technology in an appropriate and effective way as they return to the clinic addressing medical complications, which, with appropriate use, should have been prevented, or at least the risk of further progression in these complications should be reduced.

RESEARCH COLLABORATION

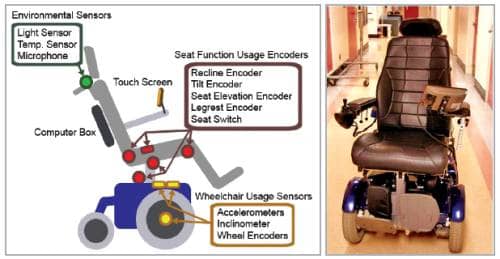

To address this problem, our research team at the University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University collaborated on the development of a wheelchair seating coach that includes a series of seat function encoders, wheelchair encoders, and environmental sensors installed on a Permobil C500 power wheelchair equipped with a full set of power seat functions. In addition, it had a single board computer synthesizing sensor information to determine the appropriate coaching protocol to assist wheelchair users for effective pressure relief and driving safety, and a touch screen delivering the coaching messages to the user via a multimedia interface. This seating coach can track and transfer data on actual PSF use such as how long a user maintains the same seating position, how often and for how long the user assumes pressure relief positions, and the sequence of using the tilt/recline/elevating legrest functions. Since the coach can be programmed by clinicians with an individualized usage prescription, the actual PSF use is also compared with prescription settings to evaluate the user’s compliance. The wheelchair battery is used as the power source for all components to allow the seating coach to be available whenever the power wheelchair is in use.3 In addition, accelerometers and light and audio sensors for context detection will allow the system to be smart enough to know the environment in which a device is used and to alter feedback display effects for appropriateness of coaching message, ie, silence the communication method in a quiet movie theater.3

The instrumentation diagram of the Virtual Coach and a picture of the actual system. It is very difficult to distinguish between a wheelchair with the Virtual Coach and a regular wheelchair, except for the touch screen.

It is very difficult to tell the difference between a wheelchair equipped with the Virtual Coach and a regular wheelchair, except for the touch screen. Engineers try to keep the instrumentation as low profile as possible to avoid increase in wheelchair dimensions and disturbance in daily activities.

It was important during the user interface design phase to conduct an end-user preference study that determined the appropriate interface modalities and coaching strategies, to make sure the coaching message would be meaningful, accepted, and not annoying to the end user. Four types of coaching scenarios, including reminders, warnings, guidance, and encouragement, as well as preferred interface modalities and stimuli, were selected. The data showed that the majority preferred an animated power wheelchair figure to illustrate the instruction for the specific task. Users also preferred to have a cartoon animation to advise them of the task they need to do.4 When provided with a choice of a static human face to simulate the effect of an animated human face, the participants commented that they would like to work with a human agent whose face is someone they knew or someone who was significant to them instead of a generic animated human agent.4

Currently, the Virtual Coach provides specific coaching messages when detecting whether a user forgets to change positions for pressure relief or uses the seating functions inappropriately. The system will be able to implement an adaptive coaching strategy where the coaching messages and feedback can change dynamically based on user compliance, responsiveness, and environment. One of the unique components of the coach is the clinician interface—a PSF usage report is provided through a VBA program designed for clinicians, displaying the PSF usage profile in a friendly format and generating spreadsheets for the record and future reference.

The Virtual Coach is entering the clinical study phase by introducing instrumented power wheelchairs into the clinical assessment. To date, we are in the process of conducting a pilot study testing the robustness and reliability of the intervention of the Virtual Coach while instrumented chairs are being used by end users within their home settings. The next phase is to introduce the coach into the real world and incorporate it into the clinical evaluation and training process. It is anticipated that the Virtual Coach will provide extensive and appropriate training within a feasible time. It is a very promising tool designed to provide feedback about the effectiveness of education and training by tracking the compliance and follow-up that will provide insight about how PSFs are actually used. In addition, the data will provide valuable evidence to support justification to third-party payors for continuation of funding for the full set of PSFs. RM

Rosemarie Cooper, MPT, ATP, Rory A. Cooper, PhD, Hsin-Yi Liu, MS, and Annmarie Kelleher, MS, OTR/L, ATP, are with the Department of Rehabilitation Science and Technology, University of Pittsburgh. For more information contact .

REFERENCES

- Lacoste M, Weiss-Lambrou R, Allard M, Dansereau J. Powered tilt/recline systems: why and how are they used? Assist Technol. 2003;15:58-68.

- Ding D, Leister E, Cooper RA, et al. Usage of tilt-in-space, recline, and elevation seating functions in natural environment of wheelchair users. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;45:973-83.

- Ding D, Liu H, Cooper R, Cooper RA, Smailagic A, Siewiorek D. Virtual coach technology for supporting self-care. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2010;21:179-94.

- Liu H, Grindle G, Chuang F-C, et al. User preferences for animation and speech properties: a survey study for developing a smart reminder to facilitate wheelchair power seat function usage. Presented at: RESNA Annual Conference; June 2010; Las Vegas.