An analysis of data from 7 years of actual cases helps fill the evidence gap about proper dosing and the health benefits of pediatric standing.

by Melissa K. Tally, PT, MPT, ATP, and Erin M. Pope, PT, MPT, ATP

This article is published as a follow-up to “Formulating Proper Dosage for Standing,” which appeared in Rehab Management’s Jan/Feb 2013 issue.

To borrow a phrase from Sir Elton John himself, “We’re still standing better than we ever were,” including the year 2013 when we presented our clinical approach to formulating proper dosage for the use of a standing device. At that time, we described how we implemented a standing protocol into the plan of care for all appropriate individuals participating in our multidisciplinary therapeutic programs and assistive technology evaluations for pediatric and adult populations. Each protocol was designed to match the unique needs of the individual, taking into consideration age, development, diagnosis, medical and physical presentation, environment, level of assistance needed, and current based evidence supporting the use of standing devices. Seven years have passed, and we are back to share what we learned during that time about standing and proper dosing.

Progress in Retrospect

In early 2013 our evidence base about dosage and the medical benefits of standing was limited. Like most clinicians and medical providers promoting the use of standers, we relied on all available resources including clinical experience and expert opinion. The available evidence repeatedly established the concepts of motor development and the therapeutic benefits of standing devices as treatment for certain physical impairments but at times were disregarded and questioned. The most documented research at the time supported a standing dosage of 45-90 minutes1 and showed benefits with the treatment of secondary complications including bone mineral density,1-3 range of motion1,4-8 and spasticity.1,7-9 Several of these benefits continue to be supported to this date. While there are still questions, they tend to be directed toward the need for more evidence to strengthen the clinical practice and expert opinion.

Evidence emerging after 2013 has been limited but has confirmed much of what was discussed in our original article. The most comprehensive systematic review about stander use to date was published later in 2013, and confirmed the above dosage recommendations and benefits.10 Research has continued to strengthen and support stander use to address treatment of secondary complications,20 specifically to maintain hip integrity and promote acetabular development,11 increase bone mineral density,12 improve range of motion and contractures13,14 and guide treatment plans of care across critical periods of development.15 In our opinion, some of the most important literature publications have addressed the importance of 24-hour postural management for patients with complex neuromotor disorders across the lifespan15,16,21,22,23 and the need to provide parent coaching and embedding treatment into daily routines and activities.16,20

Where Are We Now?

This evidence has continued to support our clinical model and approach to standing dosage across the lifespan for patients affected by neuromotor conditions. In our opinion, the benefits have only been strengthened—not refuted. There is continued need for further conversation and understanding about the effect of standing on certain body systems and its impact on secondary complications. However, there is solid baseline support that consistent use of a standing device does positively impact function, reduce secondary complications, improve overall medical, physical and social development, and positively impacts participation and the well-being of the patient.20 We would also like to state that it positively impacts the whole family.

Time-Tested Approach

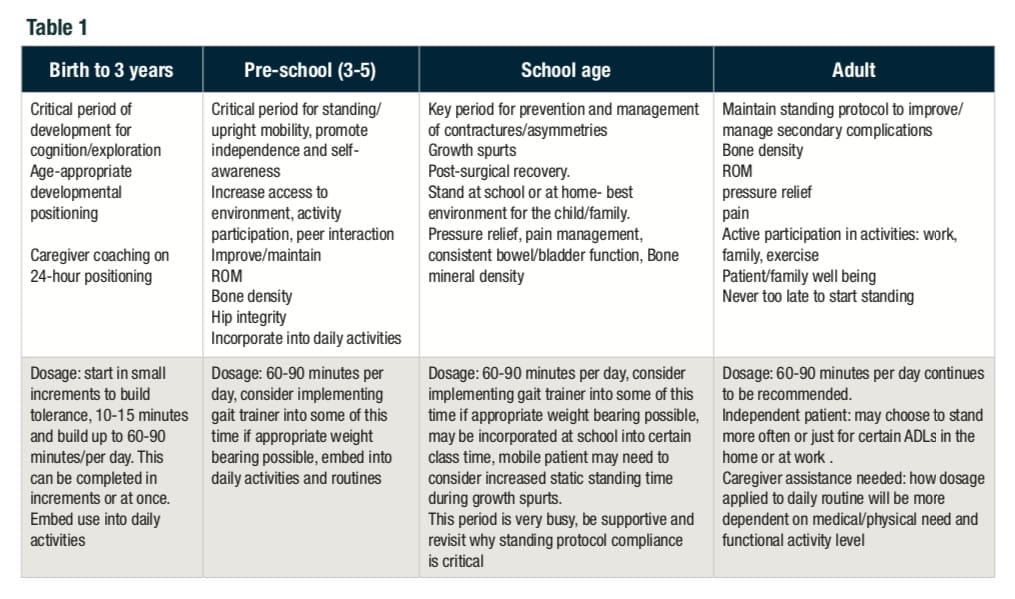

Based on our experience, opinion, and the research mentioned above, our approach to the assessment, equipment recommendation, and establishment of a standing protocol has not changed much over the last 7 years. We continue to feel strongly that implementation and compliance with a standing protocol is essential at all stages of development for a patient with a neuromuscular diagnosis. We continue to perform our evaluation per the standards of practice for recommending complex rehab technology.17 Our program has been utilizing 24-hour postural management for well over 20 years. The literature supporting this approach has strengthened our overall assessment and clinical education about the use of standing devices.21, 22, 23 We practice this model with our patients of all ages and follow their care for several years. We see the positive impacts across all areas presented in the literature. We actively implement knowledge translation of the available research and expert opinion into our clinical approach and profession education opportunities, which has allowed us to refine our recommendations for key periods of development. As the chart shows, each stage of development poses its own set of considerations and goals for the use of standing.

Standing Technologies Improve

Additionally, we have seen the standing devices available for evaluation, trial and recommendation improve in design and function during the last 7 years. Manufacturers are committed to ensuring products meet the functional, medical and postural needs of their clients as well as adhering to evidence-based guidelines. The patient and family have a variety of options to meet their medical and lifestyle needs. It is very important for them to have optimal, quality choices for complex rehab equipment.

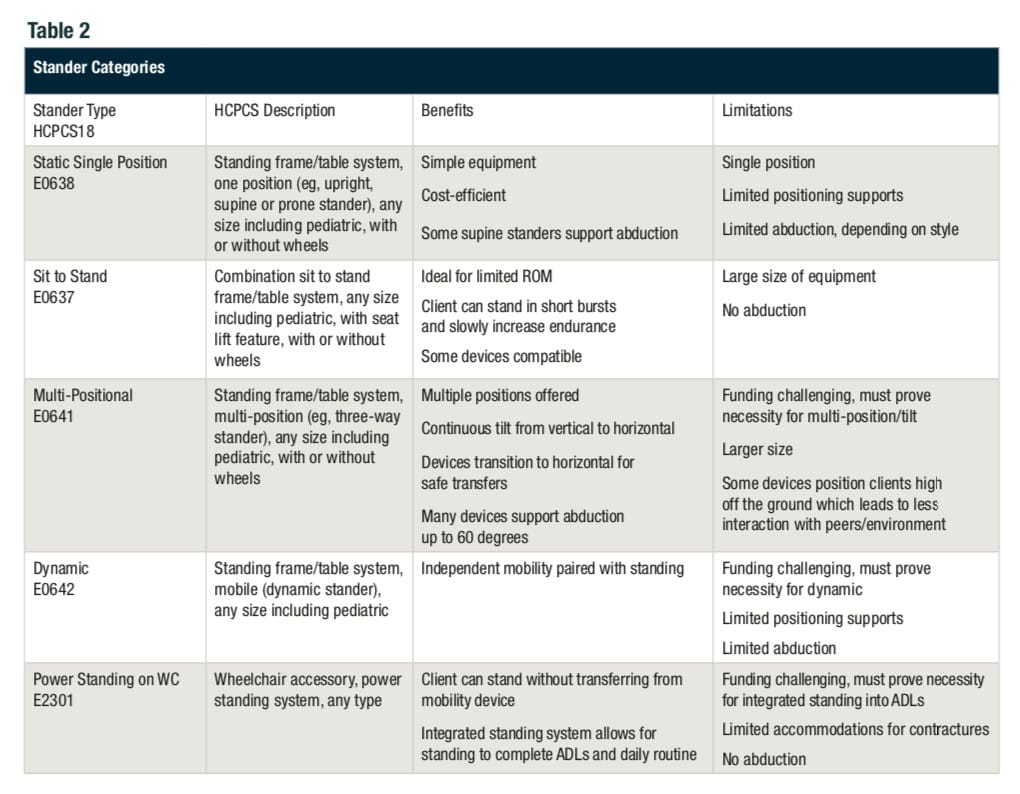

The overall clinical description for stander categories has not changed and continue to include single position (supine or prone), multi-positional, sit to stand and dynamic. The one addition, that really is not “new,” is the standing power chair. A detailed clinical assessment of the patient with adherence to the referenced standards of practice, input from the evaluation team, consideration of individual needs and equipment trials will reveal the specific category to be recommended. The trial of various models of that type of standing device will allow for final recommendation of the product. Please refer to Table 2 for specifics about stander categories and clinical justification consideration.

Timing and the Necessity of Standing

We have seen the increased literature base supporting the positive impact of standing devices, as well as the increased opportunity for clinical education on postural management and complex rehab equipment, positively impact all areas of standing. Manufacturers are improving the quality of stander design. Physicians are referring patients early and consistently across all ages and key periods of development. Families and patients are showing increased compliance with daily standing protocols and buying into 24-hour postural management. School teams are embedding standing into daily activities/routines. Perhaps most importantly, individual users are asking for access to standing for increased functional independence and access in all environments (home, school, community and work).

However, despite the evidence base and ongoing effort for knowledge translation, we continue to receive the occasional stander referral for a 3-year-old child with cerebral palsy, who has missed out on 2 years of crucial formation of their acetabulum. Some therapists and physicians continue to believe that a stander is unnecessary because the patient is either “too involved” or “too mobile.” And of course, to the chagrin of all involved, funding sources continue to be a thorn in our sides. Many payors continue to omit standing devices from their policies or conclude that the stander is “not medically necessary” or “not supported by the literature.”

Standing Firm

It is our sincere hope that continuing to bring light to the importance of standing will keep this intervention in the forefront of our minds as therapists and assistive technology practitioners. Standing is essential to maintain proper body structure and function, and literature is needed to continue to prove the efficacy of standing devices. Evidence is needed on the impact of standing on quality of life, including participation in daily activities at home and peer interactions at school. We need better-quality studies on the impact on pain and range of motion. We will continue to advocate, educate and provide practice-based evidence for all patients to have access to an appropriate standing device. RM

Melissa K. Tally, PT, MPT, ATP, and Erin M. Pope, PT, MPT, ATP, work for the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Perlman Center. The center is a multidisciplinary intensive therapy program, state-of-the-art assistive technology evaluation center and is part of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital CP program. CCHMC, 3333 Burnet Ave, Cincinnati OH 45229. [email protected]. For more information, contact [email protected].

References

- Glickman LB, Geigle PR, Paleg GS. A systematic review of supported standing programs. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2010;3(3):197-213.

- Stuberg W. Considerations related to weight-bearing programs in children with developmental disabilities. Phys Ther. 1992 Jan;72(1):35-40.

- Paleg G. Standing strong. Advance for Physical Therapists and PT Assistants. 2005;16:39

- Tremblay F, Malouin F, Richards CL, Dumas F. Effects of prolonged muscle stretch on reflex and voluntary muscle activations in children with spastic cerebral palsy. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1990;22(4):171-80.

- Gibson SK, Sprod JA, Maher CA. The use of standing frames for contracture management for nonmobile children with cerebral palsy. Int J Rehabil Res. 2009 Dec;32(4):316-23.

- Bohannon R, Larkin P. Passive ankle dorsiflexion increases in patients after a regimen of tilt table-wedge board standing. Phys Ther. 1985; 65:1676-1678.

- Baker K, Cassidy E, Rone-Adams S. Therapeutic standing for people with multiple sclerosis. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2007 Mar;14(3):104-109.

- Salem Y, Lovelace-Chandler V, Zabel RJ, McMillan AG. Effects of prolonged standing on gait in children with cerebral palsy. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2010 Feb;30(1):54-65.

- Eng JJ, Levins SM, Townson AF, Mah-Jones D, Bremner J, Huston G. Use of prolonged standing for individuals with spinal cord injuries. Phys Ther. 2001 Aug;81(8):1392-9.

- Paleg GS, Smith BA, Glickman LB. Systematic review and evidence-based clinical recommendations for dosing of pediatric supported standing programs. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2013;25(3):232-247. doi:10.1097/PEP.0b013e318299d5e7.

- Macias-Merlo L, Bagur-Calafat C, Girabent-Farrés M, A Stuberg W. Effects of the standing program with hip abduction on hip acetabular development in children with spastic diplegia cerebral palsy. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38(11):1075-1081. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2015.1100221.

- Han EY, Choi JH, Kim SH, Im SH. The effect of weight bearing on bone mineral density and bone growth in children with cerebral palsy: A randomized controlled preliminary trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(10):e5896. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000005896.

- Macias-Merlo L, Bagur-Calafat C, Girabent-Farrés M, Stuberg WA. Standing programs to promote hip flexibility in children with spastic diplegic cerebral palsy. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2015;27(3):243-249. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1097/PEP.0000000000000150.

- Capati V, Covert SY, Paleg G. Stander use for an adolescent with cerebral palsy at GMFCS level V with hip and knee contractures [published online ahead of print, 2019 Apr 4]. Assist Technol. 2019;1-7. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1080/10400435.2019.1579268.

- McLean L, Magnuson S, Gasior S. (2014) Positioning for Hip Health: A Clinical Resource, Sunny Hill Health Centre for Children BC, Canada. Poster Presentation, The 30th International Seating Symposium. March 4 – 7, 2014, Vancouver Canada.

- Novak I, Morgan C, Fahey M, et al. State of the Evidence Traffic Lights 2019: Systematic review of interventions for preventing and treating children with cerebral palsy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2020;20(2):3. Published 2020 Feb 21. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1007/s11910-020-1022-z.

- RESNA Code of Ethics and Standards of Practice. RESNA.org; https://www.resna.org/Portals/0/Documents/RESNACodeofEthics_2015.pdf. Accessed 6/15/2020.

- HCPCS E Codes. Accessed at https://www.hcpcsdata.com/Codes/E 6/15/2020.

- The Application of Wheelchair Standing Devices. RESNA.org. https://www.resna.org/Resources/Position-Papers-and-Service-Provision-Guidelines. Accessed on 6/15/2020.

- Novak I. Evidence-based diagnosis, health care, and rehabilitation for children with cerebral palsy. J Child Neurol. 2014;29(8):1141-1156. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1177/0883073814535503.

- Gericke T. Postural management for children with cerebral palsy: consensus statement. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48(4):244. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1017/S0012162206000685.

- Kittelson–Aldred T, Hoffman LA. (2017). 24-hour posture care management: Supporting people night and day. Retrieved from https://rehabpub.com/conditions/neurological/cerebral-palsy/24-hour-posture-care-management-supporting-people-night-day/.

- Schmidt R, Schmidt. (2017). 24hour posture positioning & wheelchair-seating intervention and technology procurement: evidence-based intervention effectiveness. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.22706.30402.