Scientists offer a treatment algorithm that they say could help identify patients with global (flail arm) brachial plexus injuries who could benefit from replacing their nonfunctional hand with a myoelectric prosthetic device.

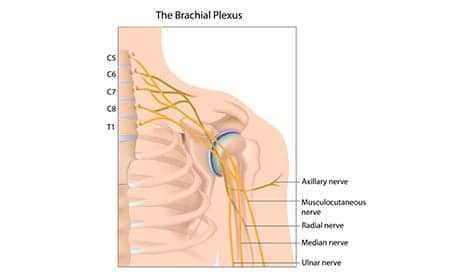

The brachial plexus is a network of sensory and motor fibers originating from spinal nerves in the lower cervical and upper thoracic spine that coalesce to form nerves that serve the shoulder, arm, and hand. A traumatic injury to the brachial plexus can cause these fibers to overstretch, sometimes avulsing (tearing) the spinal nerve roots from the spinal cord. As a result, the hand could lose nerve and muscle activity, explains a media release from Journal of Neurosurgery Publishing Group.

In an article that appears in the Journal of Neurosurgery, Laura A. Hruby, MD, and colleagues from the Medical University of Vienna and the University of Applied Sciences FH Campus (Vienna) explain the protocol, as well as recount experiences with 16 patients who sought treatment for global brachial plexus injuries at the Center for Advanced Restoration of Extremity Function in Vienna between 2011 and 2015.

The protocol is as follows, the release explains: Physical and psychological assessment of the patient to ensure that there is useful shoulder and elbow function but no motor ability or sensation in the hand, and that the patient can face the challenges ahead; identification of electromyographic signals in muscles of the forearm; and optional surgery to perform selective nerve transfer and/or transplantation of healthy muscle to improve nerve function and muscle activation in the forearm.

Additional steps are: training the patient’s brain via biofeedback, allowing the patient to target reinnervated muscles to control movement of the hand and forearm; hybrid hand fitting, in which patients are trained to use a prosthetic device with their own biosignals prior to hand amputation; effective amputation of the biological hand; and replacement of the biological hand with a myoelectric prosthetic device, followed by additional training and testing of bionic hand function.

Outcomes from five patients in whom sufficient follow-up was obtained (at least 3 months after final prosthetic fitting) are included in the study, and were assessed using the Action Research Arm Test (ARAT), the Southampton Hand Assessment Procedure (SHAP), and the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) questionnaire. The authors suggest that all five patients experienced significant improvements in their hand function, which continued through the follow-up period.

The other 11 patients were still moving through earlier steps of the algorithm, the authors state in the release.

Three of the five patients included in the study experienced severe deafferentation pain (a type of chronic pain often experienced by patients with global brachial plexus injuries). Once they became accustomed to working with the bionic hand, their pain lessened. However, when they could not wear the prosthetic device due to regular maintenance, their pain reportedly increased again within days, the authors note in the release.

Senior investigator Oskar C. Aszmann, MD, PhD, concludes in the release, “For more than 25 years, I have dealt with patients suffering from devastating peripheral nerve lesions. Bionic reconstruction, as described in this paper, has been a real game changer since it offers hope and real help for patients who otherwise have none.”

[Source(s): Journal of Neurosurgery Publishing Group, EurekAlert]