Gaze stability exercises are prescribed to reduce some types of balance disorders, including oscillopsia, which can result from vestibular hypofunction.

Photography provided by the author and Solo-Step Inc

Vestibular rehabilitation therapy (VRT) encompasses exercise therapy used to reduce dizziness in individuals with central nervous system or inner ear disorders. It is typically directed by a physical therapist with specialized training in balance and vestibular disorders, and is highly appropriate for patients with residual oscillopsia (unstable gaze) and imbalance related to stable vestibular loss from unilateral or bilateral vestibular disorders. Common ailments that may be responsive to VRT include vestibular neuritis, labyrinthitis, anterior vestibular artery ischemia, vestibular schwannoma (post-resection), Meniere’s disease, and aminoglycoside-induced bilateral vestibular loss. Individualized exercises are prescribed, and consist of eye/head movements, balance, and gait exercises with the goal of facilitating central nervous system compensation for vestibular loss.

In addition, patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) are frequently referred for VRT. BPPV is the most common peripheral vestibular disorder and is caused by displaced calcium carbonate crystals (otoconia) migrating in response to changes in head position within the affected semicircular canal or canalithiasis.1 Otoconia may adhere to the cupula (membranous encasement surrounding hair cells within the semicircular canal); this variant of BPPV is termed “cupulolithiasis.”2 Normally, otoconia are attached to the otolithic membrane within the utricle where they assist in detection of linear accelerations (namely, gravity). The debris tends to detach with age, as well as following head trauma. Other possible risk factors for BPPV are gender (female > male), osteoporosis, habitual one-sided sleeping, genetic factors, and other inner ear diseases affecting the utricle.

A major challenge facing therapists is to determine if a patient is appropriate for VRT. Many patients are referred by their primary care providers with symptoms, but without a specific medical diagnosis. The therapist’s role may involve determining if the patient’s symptoms are appropriate for VRT. In addition, the therapist needs to determine which specific rehabilitative interventions are indicated. They also might recommend further testing to clarify the source of the patient’s symptoms. Referral to an audiologist for testing, and/or referral to a neurologist or otologist/otolaryngologist with an interest in vestibular disorders, can be quite helpful in select cases. Vestibular rehabilitation services should ideally be provided at centers with access to the variety of potential services that patients with vestibular disorders might require. (For a listing of providers with an interest in vestibular disorders, go to www.vestibular.org.)

Testing equipment can be helpful for a therapist evaluating a patient with dizziness. The equipment should include a Snellen eye chart, a set of tuning forks, a high/low table with the capacity to tilt, a dense block of foam, a handheld vibrator, and an otoscope. The therapist should also have a tool to inspect eye movements when the patient is not visually fixated. Vestibular-origin nystagmus can often be suppressed by visual fixation and seen only when fixation is removed.

Frenzel lenses or infrared video goggles are commonly used for this purpose and may be connected to a monitor for observation and recording of eye movements. Recordings can be helpful for reviewing tests (without repeating them on the patient), teaching, and patient education.

THE ELEMENTS OF VESTIBULAR REHABILITATION THERAPY

An initial VRT visit typically includes the following components:

The author (left) and a client demonstrate the use of infrared video goggles, which augment observation and recording of eye movements during an examination.

- Systems review: This involves a review of the patient’s medical history and completion of screening tests when indicated. Specific attention is typically focused on: neurological conditions; cardio-vascular system disorders; endocrine system-related disorders, including diabetes; orthopedic considerations, which may alter the therapist’s approach to testing and treatment; and psychological disorders, including a history of anxiety or panic disorder.

- Review of laboratory testing: If audiologic or vestibular function tests have been completed, reviewing the results can provide insight into the nature of the patient’s dizziness. Common tests ordered may include an audiogram and ENG/VNG (electro- or video-nystagmography). A component of VNG testing is caloric testing, which involves irrigations of warm and cold water into the ear canal. The caloric test is one of the most useful measures of vestibular function, as it isolates function in each ear. The irrigations indirectly alter vestibular activity from the horizontal canal, thus providing a measure of vestibular responsiveness bilaterally. Generally, asymmetric responses of greater than approximately 25% are considered significant for unilateral vestibular hypofunction. Some centers use air, instead of water, which is considered a less reliable medium to transfer temperature. Rotational chair, VEMP (vestibular evoked myogenic potential) testing, computerized posturography, or CT/MRI of the brain and ear may also be ordered in specific cases. Detailed information on vestibular function testing is available at www.dizziness-and-balance.com.

- History regarding present complaints: Obtaining a detailed history is crucial in patients with dizziness. Typically, a careful history enables the experienced therapist to determine the potential causes of the patient’s symptom complex. A thorough history facilitates a directed physical examination. Some features that are important to inquire about in regard to the patient’s dizziness are: type (vertigo vs imbalance vs presyncope), duration/frequency, and provocative factors. The therapist should question the patient about tinnitus, hearing loss, or aural fullness. Associated audiologic complaints are more common with acoustic neuroma, Meniere’s disease, labyrinthitis, and superior canal dehiscence. Referral to an otologist is recommended in patients with dizziness and associated audiologic complaints.

- Examination: There are a growing number of bedside/office-based vestibular tests. Common special tests that may indicate vestibular dysfunction include observing for resting (spontaneous) and lateral gaze-evoked nystagmus, gaze instability with head thrusts in the plane of each semicircular canal, and post-head shake nystagmus. Examination may also include observation for nystagmus with hyperventilation, vibration to the mastoid or sternocleidomastoid muscle, and pressure (Valsalva). Head positioning tests (Hallpike and roll tests) are performed primarily to assess for BPPV. Commonly, patients with vestibular loss complain of oscillopsia, which can be assessed with dynamic visual acuity testing. Static standing balance can be assessed with eyes open and closed on a firm and unstable (foam) support surface to assess the patient’s ability to use different senses for balance. Typically, patients with vestibular dysfunction struggle to maintain stability when somatosensory and visual cues are minimized or absent. Gait should be assessed with head movement, eyes closed, and quick turns. The Fukuda step test (used to assess individuals with peripheral vestibular dysfunction or balance instability) can be performed to further assess for the presence of an uncompensated vestibular dysfunction. Review free-access video clips of the above tests at www.vestibularseminars.com.

- Evaluation: The primary focus of this step is to determine if the patient is an appropriate candidate for vestibular rehabilitation. Other management options may include referral for additional testing or medical management, especially if there are findings that are concerning and unexplained. Some patients may be completely inappropriate for VRT, which tends to be helpful in reducing consistent motion-induced spells of dizziness. It is not indicated to address exclusively spontaneous spells of dizziness, and is not appropriate for patients with no indications of vestibular dysfunction.

- Intervention: Treatment typically falls into two common categories: canalith repositioning maneuvers (CRMs) for BPPV or compensation exercises to address vestibular loss. Patients with central vestibular dysfunction and motion sensitivity may also be treated with VRT; however, there is less evidence to support VRT in this patient population.

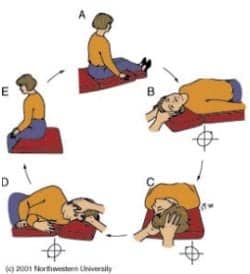

The Epley maneuver is demonstrated for right posterior canal BPPV, canalithiasis type.

Canalith repositioning maneuvers are a well-established treatment for BPPV.3 This treatment involves sequential position changes of the patient’s head, with the goal of migrating the displaced otoconia from the affected canal back to the utricle. The most common CRM for canalithiasis is an Epley maneuver.4 If appropriate, patients can be instructed in self-repositioning maneuvers to address potential recurrence, which is not uncommon.5

Vestibular compensation exercises consist of routines designed to reduce oscillopsia and imbalance. Exercises to address oscillopsia typically combine head and eye movements with the goal of maintaining image stabilization. Balance exercises focus on enhancing the use of residual sensory cues with dynamic activities. Exercises may include dynamic activities such as weight shifting, bowing, sit-to-stand transitions, step drills, gait, and pivoting. The exercises may be performed on distorted surfaces (foam/grass) or with visual cuing distorted or eliminated. In addition, patients are encouraged to participate in leisure activities that promote compensation, such as ball sports, martial arts, or dance. (Examples of common vestibular exercises can be found at www.vestibularseminars.com.)

Jeff Walter, PT, DPT, NCS, is director of the Otolaryngology Vestibular and Balance Center at Geisinger Medical Center and physical therapist for Geisinger Healthsouth at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pa. He developed www.vestibularseminars.com, a teaching Web site designed to provide information to assist clinicians in the management of dizziness and imbalance. For additional information, contact .

REFERENCES

- Parnes LS, McClure JA. Free-floating endolymph particles: a new operative finding during posterior semicircular canal occlusion. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:988-92.

- Schuknecht HF. Cupulolithiasis. Arch Otolaryngol. 1969;90: 765-78.

- Bhattacharyya N, Baugh F, Orvidas L, et al. Clinical practice guideline: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139(5 suppl 4):S47-81.

- Epley JM. The canalith repositioning procedure: for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;107:399-404.