|

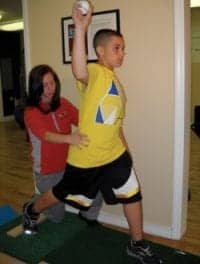

| Judith M. Smart, PT, guides patient Michelle, left, through a series of therapy exercises. Michelle’s boyfriend observes. |

Gravity is generally regarded as a good thing—it keeps the planet together! But gravity has a downside—it can limit the potential for effective physical therapy early on in a way that water does not. The physical properties of water—hydrostatic pressure, viscosity, buoyancy, and heat—make aquatic therapy a powerful and valuable adjunct to land-based therapy.

Much has been written about the advantages of the physical properties of water in therapy. Aquatic therapy promotes body awareness and balance. Hydrostatic pressure helps stabilize unstable joints while decreasing joint compression. Water adds resistance in all directions and enables patients to work harder at higher intensity levels. The buoyancy of water that displaces mass allows movement in water to be easier and less painful than when the body is subjected to stresses involved in a gravity-loaded environment. Water therapy has also been said to result in less scar formation, less atrophy, less soft tissue damage, and less adaptive shortening.

“For some patients, we have been able to do therapeutic exercises and achieve functional progress in aquatic therapy that simply could not have been done at that stage of rehabilitation any other way,” says Kim Hutchinson, PT.

|

| Tara Llana practices her strokes. |

The heat capacity of water increases peripheral circulation, relaxes muscles affected by tone or pain, and makes muscles and tendons more supple and easier to stretch. Ninety-five degrees minus 2º is a widely accepted temperature—warm enough to be slightly above skin temperature of 93º for comfort, but not hot enough to cause stress by being above the body’s 98º core temperature. Too much heat and strenuous activity together can generate excessive internal heat and stress the cardiovascular system.

Physical therapists testify that aquatic therapy can also speed up the therapeutic process following spinal cord injury (SCI) and traumatic brain injury (TBI). Therapists often observe neurological and functional improvements in the pool that are not observable on land, and can begin to work on strengthening earlier. In that way, aquatic therapy complements land-based therapies, and the combination can be very powerful. While studies that attempt to isolate factors in recovery are in process, expert consensus is that aquatic therapy is a valuable rehabilitation modality in conjunction with all other treatment modalities.

|

| Patients Marianne, center, and Scott in scuba gear. Judith M. Smart, PT, assists. |

CASE STUDY

One of our recent patients was run over through his midsection by a drunk driver. He was missing part of his pelvis, gluteus maximus, and other internal structures. His range of motion was compromised by heterotopic ossification in both hips, but his leg muscles were working. He was in a wheelchair full-time, could not stand up or walk, and could not use a tilt table because of trunk instability. At the conclusion of his first pool session with the assistance of one therapist, he ambulated 15 feet in a depth of 5 feet of water, without any assistive devices. After 2 weeks, he became ambulatory on land with a walker. He went on to become ambulatory with no assistive devices.

Water also has significant psychological benefits. Patients who are able to accomplish physical gains in the pool often feel more confident, enthusiastic, and hopeful about their overall progress in rehabilitation. It is not atypical for patients to cry in the pool sessions—tears of joy about their ability to move around by themselves, and for things they are able to accomplish. Warm water can also provide physical relief from spasticity and pain. Greater range of motion for painful or subluxed shoulders, for example, can be accomplished in aquatic therapy. Patients can also experience joy and fun in the pool, working on physical skills as they participate in creative games with their therapists and families, ie, swimming laps, swimming with masks and snorkels, swimming underwater to retrieve submerged objects, playing basketball and volleyball. Patients at Craig Hospital refer to the pool as “a happy place,” even though patients typically leave the pool physically exhausted.

According to Judy Smart, PT, “I have had patients who, within seconds for their first pool session, look at me with shock and disbelief at how effortlessly they can move in the water.”

Patients who participate in a pool program are more apt to access their community pools at home following inpatient discharge. Some of our patients have gone on to competitive disability swimming, including participation in the Paralympics. And for some patients, aquatic therapy is a precursor to their enrollment in our hospital adaptive SCUBA diving program.

|

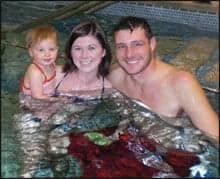

| Jesse Alberi, right, with his wife and daughter. |

|

| Therapist Judith M. Smart, PT, attaches a lift to Jesse Alberi. Alberi’s wife and daughter are in the background. |

Patients typically access our aquatic therapy program by request and/or by primary physical therapist referral and physician order. Individualized goals and treatment plans are designed collaboratively between the patient, primary PT, and the aquatic therapists, as well as frequency of sessions within the patient’s master treatment schedule. Frequency of sessions can range from one to three times per week, which is optimal in terms of balancing endurance and fatigue resulting from the physical demands of the other therapy components of the interdisciplinary rehabilitation program.

For patients with SCI and TBI, there can be dozens of different types of goals and treatments depending on diagnosis, level of injury, functional levels, types and degrees of impairments, etc. Some include, but are not limited to, pregait and gait training, upper and lower extremity strengthening, trunk and core strengthening, sitting and standing balance, coordination, range of motion, pain and spasticity management, plyometrics, aerobics, sensory stimulation and integration, and endurance.

Pools in SCI and TBI rehabilitation centers typically have either portable lifts or permanent overhead lifts for safety in patient transfers, as well as traditional stairs with handrails. Ingress and egress from the pool are patient-specific, with the goal being to use as little adaptive equipment as possible.

Individual sessions are usually ordered in the traditional sequence of:

- stretching and warm-up;

- strengthening;

- balance;

- mobility;

- a period of relaxation and cooldown.

Families are welcome to accompany injured family members in their pool sessions at Craig Hospital, and enjoy this “normalized” time together. This is particularly true of families with spouses and children. Aquatic therapists are skilled at helping patients and families feel secure and comfortable in the pool, and set an example for taking some risks, fun, and laughter. Often patients who are going through inpatient rehabilitation at the same time become friends, and these newfound friends decide to schedule their sessions in the pool at the same time. They work together, encourage each other, and often compete against one another in skills, swimming competitions, and frivolous ad-lib contests. To have five to six patients, family members, and friends in the pool at the same time makes the hard work of rehabilitation more enjoyable for all.

“Only our imagination limits what we can do in the pool,” says Sharon Blackburn, PT.

|

| left: Patient Jesse Alberi floats in therapy pool with his daughter, Bri, on his stomach. |

Pool therapists at Craig are typically physical therapists with SCI and TBI experience who have a background in aquatics. Most have backgrounds as water safety instructors, with swimming and lifesaving training. Our hospital provides all of our pool therapists with additional training in therapeutic techniques, pool management, lifesaving, and other emergency procedures. Additionally, our therapists have attended aquatic therapy and rehab institute courses (www.atri.org).

The American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) has an aquatic therapy section, and is in the process of conducting a practice analysis to determine whether there is a need for a certification process. The APTA aquatic section also has a bibliography and a handbook for providers to assist in the development of aquatic therapy programs (www.aquaticpt.org).

POOL AND CLINICAL SPECIFICATIONS

Pool specifications can vary from facility to facility. At Craig Hospital, the 14- x 21-foot, 10,000-gallon-capacity pool was recently renovated in 2007 and features access stairs with a handrail, as well as an overhead lift. The water is kept at 95º and contains a bromine bacterial agent. Filters run every 4 hours to maintain the integrity of the water.

Clinical considerations for aquatic therapy sessions within the diagnoses of SCI and TBI vary. The following are the guidelines used at our facility:

- Physician orders.

- No patients with purulent, draining wounds. Nondraining wounds are by MD approval.

- Bowel program well established—no involuntary bowel movements for 1 week prior, self-catheterization or leg bag drainage immediately prior to pool session. We allow leg bags, colostomy bags, and feeding tubes, as long as they are closed systems.

- Ability of patient to cooperate and be safe.

- Reasonable level of endurance.

- Tracheotomies closed and healed.

- Proper caution with patients who have cardiac conditions or hypertension.

- Full awareness of clinical considerations of patients by aquatic staff.

In summary, aquatic therapy allows patients with spinal cord injury and traumatic brain injury to work aggressively in rehabilitation in a warm, supportive, near-weightless environment. Because of the unique and diverse properties of water, aquatic therapy is a valuable adjunct to land-based physical therapy modalities.

Kim Hutchinson, PT, a therapeutic recreation specialist and pool therapist, has worked at Craig Hospital, Englewood, Colo, for 24 years.

Judith M. Smart, PT, has worked at Craig for 18 years on the SCI and TBI Treatment Teams and in the Multi-Trauma Unit. She has worked in the Craig pool for 2 years.

Sharon Blackburn, PT, earned her degree from the University of Florida, and has worked at Craig Hospital for 32 years in a variety of capacities, including PT supervisor for 16 years. She is one of the most nationally recognized experts in physical therapy and spinal cord injury and helped write the PVA Outcome Guidelines for SCI.

Kenneth Hosack, MA, is the director of Provider Relations at Craig Hospital. He has worked for 20 years at Craig, as a physical therapy assistant, rehabilitation counselor, and supervisor, and in his current position in administration for the past 12 years. He is well known for his 30 years of national and state leadership in the field of traumatic brain injury.