Use of the slim-cut anterior support avoids hypersensitive breast tissue post mastectomy while supporting the trunk in an upright, neutral position.

by Kirsten N. Davin, OTDR/L, ATP, SMS

The wheelchair seating and positioning arena has seen many great changes, including improved technology, updated design, enhanced attention to microclimate, and, in some cases, significantly reduced retail cost. While these are significant strides, which have been decades in the making, many clinicians are still unfamiliar with the long-term benefits of ideal pelvic and trunk positioning, as well as the relationship between said positioning and the achievement of adequate pressure relief under the contact area and preservation of skin integrity.

As part of ongoing research being performed by the author, a recent survey was conducted among more than 500 participants. This survey revealed that a sizable percentage of practicing therapists, selected from a sample of occupational and physical therapists and OT/PT assistants, are unfamiliar with the dynamic interaction between pelvic positioning and subsequent pressure relief attainment as well as the path of implementation when incorporating pelvic and trunk supports to achieve an ideal seating position in preparation for other seating applications. It was also identified that many entry-level therapists feel as though they have received a minimal amount of seating and positioning education within their therapeutic studies, and present with some degree of discomfort in real-life application of wheelchair seating assessment and troubleshooting.

Beating Pelvic Obliquity

Whether one is a veteran seating and positioning expert or an entry-level clinician, the algorithm for achieving the ideal fit is the same. Begin at the pelvis, as the pelvis is the key point of control and the foundation for all seating and positioning intervention. A small adjustment at the pelvis can produce dramatic changes to the torso and extremities, often resulting in far less intervention than what may have originally been deemed necessary.

For ease in assessment, ask the client to transfer out of the existing wheelchair seating system, and place the client on a firm seating surface, such as the mat, or in a home health setting, a straight-backed kitchen chair, or edge of bed. Assess the pelvis by visualizing the height of the iliac crests, followed by palpation of the iliac crests, and, if necessary, implementing a seat to iliac crest measurement, from the top of the seat to the iliac crest bilaterally. At this time, also assess for the presence of any posterior or anterior pelvic tilt, identifiable by the top of the pelvis tilting posteriorly or anteriorly, respectively.

If one side of the pelvis is lower than the opposing side, a pelvic obliquity is present, and is subsequently named for that low side. After identifying this obliquity, the assessing clinician must now determine if the client presents with a correctible or noncorrectible asymmetry (obliquity). The clinician can accomplish this quickly and easily by placing his or her hand under the low side of the pelvis and gently lifting the low side of the pelvis in an attempt to raise the low side of the pelvis to a height equal to that of the high side.

If the clinician is successful in neutralizing the pelvis, it can be surmised that the patient has a correctible pelvic obliquity, which can be neutralized by implementing one of two common methods: 1) Issue a wheelchair cushion with a pelvic build-up under the low side, thus mimicking the action of the clinician’s hand during assessment; and 2) Provide a single-strap (two-point) pelvic belt, with careful application to ensure it is applied at a 90-degree pull, thus the angle between the top of the wheelchair seat and the pelvic belt should measure 90 degrees. This 90-degree pull provides a counterforce to the pelvic obliquity force, which is creating the pelvic rise.

If the clinician is not successful in neutralizing the pelvis and the obliquity persists despite an attempt at neutralization, the client presents with a noncorrectible pelvic obliquity. Noncorrectible pelvic asymmetries may be addressed by providing a wheelchair cushion with a pelvic build-up under the high side of the pelvis, thus offering full surface area distribution, resulting in pressure relief and improved stability.

Following pelvic assessment and the implementation of a method of pelvic stability, the clinician must evaluate the trunk and identify any lateral deviation or forward flexion. If either is identified, lateral supports—either free mounted, or incorporated into the seat back or the application of a variety of anterior support options—may be warranted. It is only after careful assessment of the pelvis and trunk have been completed that the clinician may then assess the cervical position and determine the upper and lower extremity needs.

Always Consider the Microclimate

Whether fitting a client with a simple manual chair with a basic seating system, or an extensive power chair with tilt, recline, head-array controls, and more, it is imperative to consider pelvic and trunk positioning, and first achieve stability in order to allow the client to be successful in activities of daily living and achieve their seating goals. During this process, steps to provide an ideal microclimate must be considered as well. Microclimate can generally be defined as the condition of the area between a seating component and the client, and is comprised of three factors: heat, moisture, and pressure. Successful seating must include examination of the client’s microclimate and an effort to reduce the three above factors in order to prevent skin breakdown.

The Importance of Diagnosis-Specific Product Application

It is imperative to understand not only the general application of product lines, but to fully assess the intricate relationship of diagnosis to product. Whereas multiple types of product lines exist for the same general application, it is critical to consider the specific needs a client presents with and utilize that knowledge to select equipment that will result in the assurance of exceptional wheelchair tolerance and improved patient outcomes.

Anterior Support Considerations: A Case Study

When implementing anterior supports, the therapist has a plethora of products to choose from. Therefore, it is important that the assessing therapist ask himself or herself what specific qualities of the existing anterior support options are necessary to provide the client with the most ideal fit.

The author of this article, who is an evaluating therapist, recently faced this challenge while performing a wheelchair evaluation for a 48-year-old female patient who had been fighting metastatic breast cancer for years. Physicians initially attempted to treat the patient conservatively, with chemotherapy and radiation, which initially produced positive outcomes, as evidenced by a reduction in lesions and no known metastasis. The patient is the mother of two children, ages 18 years and 20 years, the younger of whom was to graduate from high school in the coming months, while the older one was to be married a few weeks later. Three years post original diagnosis, she learned the cancer had progressed, thus requiring a dual mastectomy, as well as continued chemotherapy to battle the recently discovered metastasis to the spine.

Due to the expected longevity and intensity of cancer treatment, coupled with the patient’s extreme weakness, chronic pain, and spinal involvement, her physician ordered an occupational therapy evaluation for a power wheelchair with the appropriate seating system in an effort to obtain improved stability, sitting tolerance, and pressure relief. The decision was also made in part to afford her the opportunity to participate in and attend the events leading up to her daughters’ graduation and wedding.

As previously noted, the first step in any successful seating evaluation is pelvic assessment. She presented with decreased pelvic stability, and a minimal, correctable right pelvic obliquity, and thus was provided with a gel-based pressure-relieving cushion to allow for full pelvic engulfment, and a single-strap, (two point) pelvic belt, applied at 90 degrees of pull, thus stabilizing the pelvis, and providing a foundation for trunk stabilization. Despite successful pelvic stabilization, due to chronic weakness and limited endurance, she routinely presented with a forward flexed trunk, which was not defined as a true kyphosis, but rather a result of this long-term core weakness and spinal involvement.

An anterior support was necessary to allow the patient’s torso to be supported while in a seated position in order to improve wheelchair tolerance, aid in proper seating/positioning, and conserve her energy for activities. Meeting all of these objectives would, thus, allow her to direct her efforts toward the activity, and not toward the fight to maintain an upright sitting posture. Extensive product assessment was performed prior to implementing an anterior trunk support, as the client presented with severe pain and extreme hypersensitivity at the site of her double mastectomy, and was unable to tolerate most clothing over the surgical site, let alone an aggressive, strong-holding anterior support or chest strap.

The only style of anterior support the client could tolerate was a slim-cut, stretch, anterior trunk support (depicted in the image on page 16). This particular support is quite thin, measuring only 1 inch at the narrowest point, thus providing the necessary anterior torso support, while avoiding the hypersensitive surgical areas. As an added benefit, the breathability and attention to microclimate this support offered ensured a reduced risk of skin breakdown, as this support was being implemented upon previously compromised skin. If additional trunk support would be necessary in the future or should eventual lateral assist be required, it was noted that the lateral with its extreme adjustability in multiple planes would offer adequate lateral support despite weight gain and the capability for repositioning and renewed pad placement should skin breakdown at the torso be a risk.

This client’s wheelchair tolerance, positioning, and sitting capacity immediately increased as a result of implementing the slim-cut anterior support, as did her motivation and spirit as she was no longer fighting to remain upright and balanced in the chair against gravity and severe weakness. Rather, she was able to rely on the anterior support, and see her youngest graduate from high school and her oldest say her vows. This single piece of carefully selected equipment resulted in the ability to spend hours in her wheelchair rather than only 8 to 10 minutes, as was the situation prior to assessment.

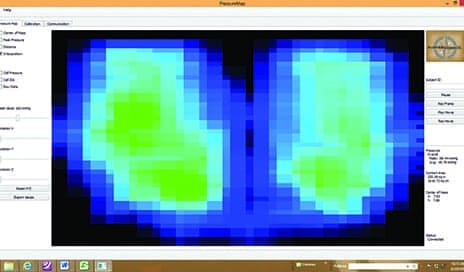

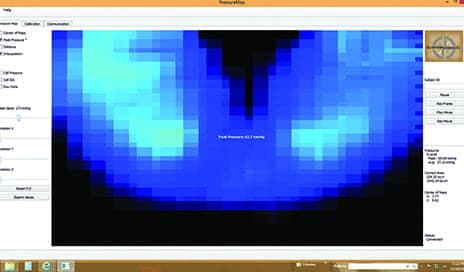

Increased pressures under the low side of the pelvis often result in pressure-related wounds affiliated with pelvic obliquity.

A flexible pelvic obliquity is evident as the clinician is able to return the client’s pelvis to a neutral position, thus achieving far improved pressures under the contact area.

Expanding the Diagnosis-Specific Approach

Advances in manufacturing and engineering have enabled suppliers to develop seating and positioning accessories that are more tailored than ever to the specific needs of a mobility device user. Drive controls are one category where these advances have expanded the control and performance users are able to exercise over their mobility devices. One of the current systems designed to provide advanced wheelchair drive control is built around a central processing unit designed to operate with a specific programming software package that expands switch site access and usability for wheelchair users who have limited functional ability. The system, which is engineered to be customized with up to eight additional switches of any type, also can provide a real-time user interface environment.

Seat back support bases are now also designed to be customizable to meet a client’s highly specific needs. Bi-angular back modification can be useful when additional horizontal adjustment is needed, and contoured back modification can be used to increase lateral supports. Custom molded seat cushions, too, can be used in cases where a highly tailored fit is required, especially in cases of very complex orthopedic asymmetries or tone abnormalities. Computer-assisted manufacturing can be used in the production of today’s custom molded seating to enhance stability and make support more precise.

Likewise, the current product lines of adductors and abductors can bring lower limbs into better alignment, keep them from unintentionally contacting wheelchair surfaces, and provide greater comfort and support to the mobility device user. Some models provide flip-down functionality to enhance ease of use.

Veteran or New-Hire… The Process Remains the Same

Successful seating begins at the pelvis, and is achieved through careful stabilization of the pelvis, trunk, and extremities, as well as attention to microclimate. Regardless of the level of the client’s involvement, the algorithm and process remain constant. Effective application of these techniques will aid in achieving seating success and subsequent improvement in microclimate, pressure relief, and functional outcomes. RM

Kirsten N. Davin, OTDR/L, ATP, SMS, owner of Escape Mobility Solutions LLC, Pleasant Plains, Ill, specializes in the provision of wheelchair seating, positioning, and assistive technology. She is a clinical consultant for Adaptive Engineering Laboratories as well as Patterson Medical, and nationally known for her continuing education seminars via Vyne Education, formerly Cross Country Education. Davin has been an occupational therapist at Memorial Medical Center in Springfield, Ill, for 15 years, is currently an adjunct faculty member, teaching anatomy/physiology at Lincoln Land Community College, and was recently named VGM’s Home Medical Equipment – Woman of the Year for 2016. For more information, contact [email protected].