An important component of treating the acutely injured worker

Paramedic simulating chest compressions using a disc designed to promote work bent over in a kneeling position. By using adjustable racks, this exercise can be modified to simulate chest compressions in a stooping position/elevated seated position. Stooping chest compressions are required during transport of patients in an ambulance.

One of the most difficult decisions that has to be made when an employee sustains an injury serious enough to cause time off work or restricted duty is whether and when the employee can return to full duty. Typically, the physician must make the decision regarding return to work, but seldom has the physician seen the job description or gone to the worksite to observe the job being performed. In addition, the physician does not generally test the patient’s function. The physician usually bases the return-to-work decision on the therapist’s progress note, which includes range of motion, manual muscle tests, pain score, and willingness to participate in therapy. Alternatively, decisions are made about imaging studies or x-rays. These measurements, although important, do not necessarily correlate to functional tasks. Without information about the patient’s work-related functional abilities and the functional demands of the job, the return to work decision can amount to little more than clinical guesswork.

If the employee returns to work too soon, weakness or decreased motion may create another injury to the same or a different body part. If the clinical guesswork is too conservative, patients will spend unnecessary days out of work and waste valuable dollars in benefits. Physical therapists can play an important role in bridging this gap by providing functional information for the return-to-work process. By providing a comparison of the patient’s functional abilities to the essential physical functions of the job, the return-to-work decision is based on objective data rather than clinical guesswork.

Optimally, the therapist will have access to a job description with detailed information regarding physical functional job demands. If a job description is unavailable or has incomplete information, the next best option is to conduct a job site visit. If a job site visit is not feasible, then it becomes vitally important to interview a supervisor or incumbent who knows the job. Once the job demands have been identified, the functional screening can begin.

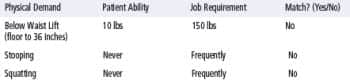

Initial Functional Testing

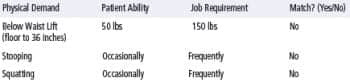

Functional Testing at the End of 3rd Visit

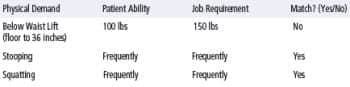

Functional Testing after 6th Visit

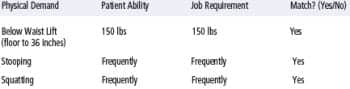

Functional Testing at the End of 9th Visit (Work Conditioning Initiated at the beginning of week three)

Functional return-to-work screening involves periodically testing three to four of the most challenging physical job demands throughout the acute and subacute phases of outpatient physical therapy. The employee’s tested ability is then matched with the job demands. Functional testing eliminates the clinical guesswork regarding the tasks the employee is capable of performing, and, therefore, is an essential tool for the professionals involved in the patient’s treatment and recovery. The therapist can use the objective data from the screen to progress the patient’s work simulation activities. The results of the testing also provide the physician, case manager, employer, and insurance carrier with objective information for light duty work or progression from off work to light duty work. As a result, case managers and employers can better communicate the needs of the employee to human resources and the front line supervisors. The physician has a clear picture of the patient’s progression relative to job demands. The case manager can also paint a clearer picture of the patient’s return-to-work status to the employer. The employee feels that the clinician understands the job demands and their needs.

CASE EXAMPLE # 1:

A 40-year-old female paramedic with a diagnosis of “thoracic pain” was evaluated in physical therapy 2 months post injury. Patient reportedly lost her balance, falling down into a sitting position with knees extended (long sitting). As a result of this fall, the patient sustained a coccyx fracture. At the time of initial physical therapy evaluation, she had been off work for 2 months. A job description was obtained through case management. During the initial evaluation, the patient was highly motivated to return to work but also afraid to move secondary to increased pain and spasms. The patient reviewed the job description with her therapist. The three most challenging job demands included a 150 lb Floor to Waist Lift, Stooping (forward bending with knees relatively straight) frequently (defined by the US Department of Labor as up to two-thirds of the work day), and Crouching/Squatting frequently. The patient expressed great concern about all lifting and forward bending.

At the end of the third visit, substantial gain was made through pain reduction, postural re-education, back safety, and lift education.

After the sixth visit, stooping and squatting had greatly improved, but the patient could not yet lift 150 lbs. The patient returned to the physician with functional testing results. The therapist noted concerns with deconditioning secondary to the 2-month layoff from work. Light duty and graded return to work were not available for this patient; therefore, work conditioning was requested by the therapist. The physician granted the therapist’s request for work conditioning for a period of 2 weeks.

The patient was able to progress to a full 8 hours of work conditioning along with matching all of the job demands. The therapist contacted the case manager and physician to request an early release to full duty along with two additional visits as needed upon completion of the first 12-hour work shift by patient. The patient returned to full duty without any issues. The physician, case manager, and patient were all pleased with the return-to-work decision and outcomes.

Initial Functional Testing

Functional Testing at the End of Week 1

CASE EXAMPLE # 2

A 45-year-old female sustained a low back sprain lifting boxes on the job and was referred to our clinic after having two courses of physical therapy at other facilities. During the initial evaluation at the third facility, the patient stated, “The first physical therapy clinic rushed me into lifting day 1 without addressing my pain. I was immediately sent back to work performing my regular job duties. The second clinic just massaged my back, which felt great but did not help me perform my job duties.” At this third facility, the patient’s job description was obtained along with other intake information and reviewed by the patient and therapist. At the second visit, the patient stated that suddenly all back pain is resolved and she feels capable of performing her job. She also mentioned that a new job has become available within her company. However, she also shared that she will be unable to interview for this position as long as she is on light duty. A physical therapy evaluation reveals normal manual muscle testing, slight deficits in lumbar ROM, and 0/10 pain.

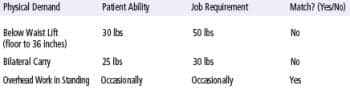

The therapist’s concern is that the patient wants this new job, regardless of whether her physical functional abilities meet the physical demands of the job. To answer the job match question, the therapist initiated functional return-to-work testing, which included a floor to waist lifting (50 lb requirement), bilateral carry (30 lb requirement) and overhead work in standing (occasionally or up to one-third of the day).

The case manager was called immediately after the functional testing. The patient’s test results were discussed along with her new motivation for returning to work. The therapist recommended moving up the follow-up visit with the physician to 1 week from the initial functional testing.

With the functional test results at the end of week 1 in hand, the patient had objective data to support her subjective statements regarding the ability to perform the job. She was immediately returned to full duty. The physician, case manager, employer, and employee were all pleased with the outcome. The new motivation was acknowledged in her recovery along with the objective baseline testing that provided evidence for the physician she was ready to return to work.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

These two cases provide examples of how functional testing can be incorporated into outpatient management of the acute/subacute injured employee. Traditional therapy tests and measures help the therapist validate and understand the patient’s current impairments. Functional testing helps all parties understand the job demands an employee can perform and provides critical information for the return-to-work decision. Providing this critical information can greatly enhance the value of physical therapy for the payors, case managers, and physicians.

Ryan Hunt, DPT, CSCS, is outpatient services manager for ErgoScience Inc, Birmingham, Ala.

Deborah Lechner, PT, MS, is founder and president of ErgoScience Inc. She has more than 25 years of clinical experience as well as an extensive research background. For more information, contact .