Proactivity and thorough skin assessments for the bariatric patient with SCI can help provide safe, cost-effective treatment.

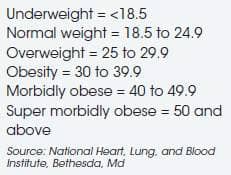

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a catastrophic condition that often results in motor and/or sensory deficits for the individual. Concurrently, many people with SCI have impaired mobility following their injury. The combination of these issues can put the injured person at high risk for costly medical complications. One such secondary complication is skin compromise or wound development that may require surgical intervention or an extended hospitalization or rehabilitative stay. When the medical condition of morbid obesity is combined with the catastrophic effects of SCI, the potential risk for skin compromise is multiplied. The prevalence of obesity in the United States has increased by 30% in the past decade from 25% to 33% of the population. Six million Americans are morbidly obese.1 Individuals who are classified as obese have a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or higher. Morbidly obese individuals have a BMI of 40 to 49.9, and a super morbidly obese individual’s BMI is 50 or higher (Table 1).

The condition of morbid obesity is growing to epidemic proportions and creating challenges for the medical community. The comorbidities associated with obesity are well known and include, but are not limited to, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hypercoagulation, type II diabetes, coronary heart disease, hernia, venous thrombosis, depression, low self-esteem, isolation, unemployment, and discrimination.3 Secondary complications that may occur following spinal cord injury—such as skin compromise—may occur at an exponential rate when combined with obesity.

The cost of treating a pressure ulcer can span from a minimum of $40,0002 to as much as $150,000 from discovery to complete healing, with some wounds never healing in persons with underlying diseases.2,4 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), as part of the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005, introduced a plan to cut cost by rejecting payment for some secondary diagnoses that are deemed preventable. This plan went into effect in October 2008. As such, skin ulcers are subject to additional scrutiny with respect to payment.2,4

TABLE 1. BODY MASS INDEX CATEGORIES2

The Shepherd Center (SC) in Atlanta, which has developed a system of care for persons with SCI, has seen an increasing number of morbidly obese spinal cord injured patients. An interdisciplinary group of health care providers at SC determined the need to be proactive and developed a task force and strategic plan to assess and manage this patient population. The task force determined the clinical staff would adopt and operate on the best practice of “safe patient handling,” explained as follows5,6:

Patients have the right to expect:

- Enough staff members and equipment to turn them safely to prevent shearing injuries

Clinicians have the right to expect:

- Not to injure themselves when turning patients

- To have help from other clinicians when turning bariatric patients

After reviewing our experience with past patients who had the combined problem of acute SCI and morbid obesity, the task force and additional clinical staff identified a list of high risk factors and interventions. This list is now part of the skin care policy, and used to guide staff members who work with these patients (Table 2).

Planning for these patients begins prior to admissions during the referral process. The admission team proactively alerts key team members regarding the proposed admission of an individual who has either a SCI or a brain injury who is morbidly obese. This prompts the team to prepare for the patient based on the established guidelines for high risk patients.

A mandatory interdisciplinary assessment involving participation from the wound care specialty nurse, the primary care rehabilitation nurse, nursing technician, dietician, physical therapist, and occupational therapist was developed to create a comprehensive plan of care. The initial assessment of the treating rehabilitation team will trigger events based on the objective findings.

TABLE 2. SKIN TEAM GUIDELINES

HIGH-RISK PATIENTS FOR PRESSURE ULCER DEVELOPMENT

- Patients whose weight is greater than or equal to 170% or less than or equal to 80% of ideal body weight (IBW) or equal to or greater than 300 pounds. Although BMI is the measure used in most of the literature, SC has chosen to use IBW as a measure of choice, as it can be adjusted for the medical condition of SCI and is a more accurate measure for this population.7

- Patients who are on/weaning from the ventilator or who have untreated/ undiagnosed sleep apnea.

- Patients with poor nutrition (pre- albumin below 15).

- Patients with moisture in skin folds and creases.

- Patients who are noncompliant.

- Patients with low arousal and/or low cognition.

- Patients who have had a previous wound.

- Patients diagnosed with tetraplegia.

- Patients who are age 65 years or older (geriatric).

- Patients who are on bed rest.

- Patients who have pain that interferes with proper positioning.

- Patients presenting postural align- ment problems (leaning) in the wheelchair.

- Patients presenting difficulties for staff maneuvering, transferring, and positioning.

- Patients using an orthotic device.

RECOMMENDED INTERVENTIONS TO ADDRESS THE RISK FACTORS

- Use turn teams with at least two staff for positioning in bed and in/out of wheelchair.

- Use repositioning slings for turns and positioning in bed to avoid shear forces.

- Use sliders and patient boosters appropriately. These are not appropriate to use on specialty bariatric mattresses that have low shear covering. Usually not necessary to use in conjunction with repositioning slings.

- Skin assessment should include visu- alization of skin from head to toe and palpation of sacral and ischial areas at least once per shift.

- Special attention must be given to skin folds and at all insertion sites of tubes (rectal, Foley, peg, and leg bag straps) taking care to fully expose them.

- Skin team to initiate orders for weekly scheduling of team assessment (PT, OT, and rehab nurse).

- The patient will have screening at the physician’s discretion for sleep apnea and/or diabetes with A1C.

- The bariatric support surface (specialty mattress) ordered and in place prior to admission.

- Seating clinic for pressure mapping and postural correction initiated at admission.

- Skin team to see all patients who weigh more than 300 pounds one time per week.

- Initiate sitting time for 3 hours with every 30 minutes pressure relief if skin on sitting surface is intact. Progress the sitting schedule slowly with frequent skin inspections. If changes are made to the cushion, the sitting schedule will be restarted at the 3-hour level. Educate the patient and family regarding repositioning when leaning and/or sliding forward in the wheelchair.

Figure 1. Multiple skin folds, abdominal panis not shown.

Figure 2. Skin discoloration, acanthosis nigricans.

Figure 3. Inspecting every inch of the skin folds. This skin fold is of the lower abdomen and is contiguous with abdominal panis. At this point, the skin fold overlap is greater than 5 inches, accenting the difficulty that could be encountered during a rigorous weekly skin inspection.

While all interventions listed above are deemed extremely important to the success of the overall skin management of this patient population, interventions 5 and 6 are highlighted above with emphasis on the importance of the daily and weekly skin assessments in addressing good skin care maintenance.

The process for ensuring that the weekly team assessments happen in addition to conscientious daily care provided by the nursing staff is assigned in the skin policy of the program. The skin policy is a shared policy for all programs of the rehabilitation center. The physical and occupational therapists are the designated staff responsible for entering this appointment on the patient’s schedule. The PT and/or OT will coordinate an appropriate time with the primary nurse and enter the agreed upon time on the patient’s schedule. Putting the appointment on the schedule indicates to all staff the importance of taking special time to further ensure our commitment to maintaining the skin in excellent condition.

A thorough skin assessment for the bariatric patient with SCI presents a more laborious task than might be expected. This task for an average sized patient usually takes 5 minutes to complete, but, for the morbidly obese SCI patient, can take as many as two to four staff members and more than 30 minutes to complete. However, despite the arduousness of this task, it has proved invaluable in identifying areas of skin compromise for these patients.

Skin folds in the morbidly obese individual are numerous and sometimes very difficult to visualize. Additionally, these folds can hold moisture, harbor bacteria, cause odor as well as trap objects, all leading to skin breakdown.2,4 Care of the skin in the folds should be approached cautiously, as it can be very fragile and easily damaged (Figures 1, 2, and 3).

This is a labor-intensive task that requires the staff to visually inspect every inch of the patient’s skin from head to toe. Additionally, all bony prominences are palpated. This is done very methodically by lifting and separating all skin folds, which can be quite numerous (see Figure 3). All broken skin will be photographed and documented for tracking. Depending on the difficulty of positioning the patient, flashlights and mirrors strategically placed will be used to ensure good visualization and effective teaching for the patient. Often this weekly team assessment reveals problems that have not been previously documented. Of course, any established skin treatments also will be performed during this inspection.

This weekly team assessment has heightened awareness about the differences in skin issues among this population. Having multiple sets of eyes evaluating the skin at the same time has hastened our learning and encouraged a more conscientious approach among the rehabilitation staff in this area. The investment of the staff also makes a positive value statement to the patient. It is hoped that patients will internalize similarly for themselves.

In summary, the trend of our population becoming heavier is expected to continue. Hospital administrators and health care professionals must be committed to better preparation for the growing number of morbidly obese clients. Serving the morbidly obese client requires increased staff and specialized equipment. The Shepherd Center continues to look for ways to be more effective in its approach and develop methods to provide safe, appropriate, and cost-effective treatment for all populations it serves.

Myrtice Atrice, BS, PT, presently works as a Therapy Clinical Manager at the Shepherd Center in Atlanta. Atrice has practiced physical therapy for 37 years with 32 years at the Shepherd Center treating spinal cord injured clients. Her areas of expertise include SCI rehabilitation inpatient and outpatient, SCI skin management pre- and post-operative, wound care certification, orthotic management of the SCI client throughout the continuum, and new technology for ambulation of the SCI client. For more information, contact .

REFERENCES

- Gallagher S, Arzouman J, Lacovara J, et al. Criteria-based protocols and the obese patient: preplanning care for a high risk population. Ostomy Wound Management. 2004;450(5):32-4.

- Mathison CJ. Skin and wound care challenges in the hospitalized morbidly obese patient. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2003;30(2):78-83.

- Rush A. Bariatric care: pressure ulcer prevention. Wound Essentials. 2009;4:68-74.

- Gallagher Camden S. Pressure ulcers, CMS changes, and patients of size: what are the issues? Bariatric Times. December 2008.

- Blackett A, Gallagher S, Dugan S, et al. Caring for persons with bariatric health care issues. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2011;38:133-138.

- Ayello EA, Capitulo KL, Fife CE, et al. Legal issues in the care of pressure ulcer patients: key concepts for health care providers: a consensus paper from the International Expert Wound Care Advisory Panel. J Palliative Med. 2009;12:995-1008.

- Pronsky Z. Food Medication Interactions. 15th ed. Birchrunville, Pa: Food Medication Interactions; 2008.