|

| The open environment of the Physical Therapy Institute at CATZ provides a visual landscape of activity and progress the facility’s founders say is inspirational to clients. |

The monochrome exterior of the building a block from the route of the Rose Parade in Pasadena, Calif, invites curiosity. It is a behemoth quadrilateral finished in flat black, and abutted by an asphalt parking lot. Within the structure looms all 14,000 square feet of the Physical Therapy Institute at the Competitive Athlete Training Zone (CATZ)—space enough to hangar a Boeing 737 and still have room for workouts beneath the wings.

The bigness of the facility, its creators hint, is medically necessary.

“We wanted it to be a vibrant, healing environment,” Jim Liston, PT, says. “Someone getting physical therapy in this big, open space can sit on a table and see someone who, several months ago, may have had the same injury but is now over on the track or on the turf running or sprinting.

“It can be an inspiration to someone who is just beginning therapy,” he says.

Liston and Kevin Wentz, PT, cofounders of CATZ, began their practice in a much smaller facility in Pasadena in 1992. The 3,000 square feet of open space within the clinic evaporated quickly as session upon session of movement-based rehabilitation rolled on between their walls.

At the time, Liston says, he and Wentz tended to deal with growth issues by “knocking down walls, and knocking down walls, until we had about 6,000 square feet of poorly designed space.”

High school athletes began turning out in increasing numbers among the general therapy population at the clinic to participate in the sports performance programs Liston and Wentz were offering. The expansion spurred Liston and Wentz to reinvent their original facility, and by 1996 they cut the ribbon on the sports-centric CATZ. A subsequent expansion in April 2007 again transformed the clinic into its present form and location where Liston and Wentz are able to stage the free movement programs they conceived while working as trainer and therapist, respectively, for the Los Angeles Galaxy professional soccer team.

Nearly one third of CATZ consists of open turf, which, Wentz says, enables PTs to realistically measure an individual’s functional gains by placing them into unscripted, unpracticed movement patterns conducted—if necessary—at full speed. Wentz believes that, since the nature of sport itself is chaotic, the ability to assess how an individual reacts extemporaneously—and in real time—provides the most meaningful barometer of progress.

“You take what you learn from the pros but drop it down to a level that’s appropriate for the person you’re rehabbing,” Liston says.

Wentz, who was responsible for rehabbing Major League Soccer superstar Cobi Jones, realized that for athletes to be prepared for a return to play meant their functional level had to be measured by real performance, rather than a computerized, machine assessment. Taking advantage of the clinic’s expansive floor, Wentz says he can now gauge the completeness of a rehabilitation program in a way other facilities cannot.

|

| Kevin Wentz, PT, cofounder of CATZ, stretches a client. Wentz says the expanse of the facility allows him to conduct assessments built on “real life,” reactive movement. |

“For a lot of people, ‘agility’ means putting out some cones and running patterns,” Wentz says, “But if the pattern is known—and it usually is—no one’s going to hurt themselves on it. If you have to react to something, like an opponent or a ball that forces you to run in different directions at different speeds, to cut and decelerate—then you have to change with whatever is in front of you, because you don’t know the pattern,” Wentz says.

“Before I’ll send someone back to play, they have to pass my functional tests, which means we move onto the turf and go into live situations that require reactive types of movement,” he adds.

TOOLS OF THE TRADE

The wide-open floor space of the facility leaves Wentz and his staff of PTs with few equipment needs. Dumbbells, sandbags, bands, and balls are still in his inventory as well as traditional modalities such as ultrasound, laser, and electrical stimulation, which all make the cut. But, Wentz points out, the bulk of the work is performed by therapists who work hands-on stretching clients to boost range of motion, or doing soft tissue work to reduce swelling.

Wentz reveals the clinic’s hottest new pieces of gear are “body weight and gravity.”

“If a person had knee surgery and they’re having difficulty walking or going down stairs because their quadriceps is weak, putting them in a machine puts them into a totally different environment where they’re no longer moving against gravity,” Wentz says.

He explains that the strength a patient might build in the quadriceps by doing knee extensions on a machine is achieved without regard to surrounding musculature, creating a type of strength that is “foreign” to the nervous system.

“We get off the machine and have to wonder if that strength will carry over and correct the individual’s faulty gait pattern,” Wentz says. “It’s hard to think that it will.”

Wentz offers a case in point. “Every knee patient, no matter what diagnosis—surgery or no surgery—used to be put on an isokinetic testing and training machine,” Wentz recalls. “Patients who had undergone ACL reconstructions would be tested on the device 2 weeks after surgery, with the involved knee registering a deficit as low as 40% of the good knee.

“Patients would continue to train on the device and test at regular intervals. Within 4 or 5 weeks after surgery, the device would say the patient’s strength level was 100%.

“Then I’d see these same people limp past the clinic and I’d think, ‘Wait a minute! The machine told me they’re 100%,'” Wentz says.

The patients, Wentz discovered, were able to learn, memorize, and proficiently execute exactly the motions for which they were being tested, producing functional responses specific to what the device had asked. “So now the machine says the strength in that leg equals 100%,” Wentz says, “but functionally, in the real world, it meant zero.”

The open turf and clear lines of sight at CATZ, however, make it nearly impossible to misjudge the true level of a patient’s recovery.

“I can pretty closely re-create in our clinic what’s going to be asked of an athlete on the field,” Wentz says. “If I take someone who has an unstable knee out to the turf and do some reactive drills with them, and if they’re still limping, they realize they’re not ready to return to the sport.

“Athletes want to get to the field ASAP. When they move with a limp they know in their hearts they’re not ready.”

TEACHING OWNERSHIP

“‘Dedicated to keeping you active’ is our tag line for physical therapy,” Liston says, then follows up, “but we should say, ‘Dedicated to teaching you to own activity.'”

|

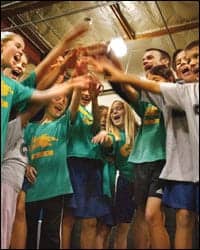

| Physical rehabilitation, sports training, and activity programs conducted across age groups and ability levels foster a sense of community at the CATZ facility in Pasadena, Calif. |

That thinking pervades even the most nascent level of CATZ patrons, where children as young as age 5 participate in “play” programs that promote physical activity and wellness. Liston says the programs also help bridge what he feels is a considerable gap in the current state of physical education in public schools.

“My kindergarten-age daughter played Steal the Bacon for her PE class one day,” Liston recalls, “and I asked her, ‘How many times did you get to run?'”

“And she’d say, ‘I was so lucky, Daddy—they called my number twice!'”

The incident sparked Liston to take an active role in changing the culture of physical education at the school. His efforts carried over into a full-blown outreach program deployed by CATZ to the local community—at no charge—that provided coaching and education resources to local schools as well as park and recreation programs. The efforts raised the visibility of CATZ throughout Pasadena and, according to Liston, created a “significant” positive impact on the facility’s bottom line.

“Our community outreach is designed to impact as many children as we can, especially at the elementary school level,” Liston explains, “If you catch children in that age group early enough, some of these problems we’re seeing with obesity, inactivity, and diabetes can be reduced or, in some cases, eliminated.”

CHANGING OF THE GUARD

Liston and Wentz did not want CATZ to exist only as a gargantuan warehouse inhabited by tables and turf, where clients toiled in anonymity. The two felt that providing the new space with an atmosphere that felt supportive and healing to clients would be an essential part of the enterprise’s success. Rather than hope for serendipity to provide this environment, Liston and Wentz created an employee manual that outlines critical maxims they determined must be practiced facility-wide.

“You always want to make people feel welcome,” Liston says. “That’s number one. That’s big. If you want someone to ‘own’ their rehab or fitness program, then they have to feel welcome coming in, no matter who they’re dealing with.”

Liston says clients must feel it is okay to make mistakes. “You talk and you say you want [them] to make mistakes because that’s how you get better. It’s by praising and encouraging people that they’ll want to try it again.”

CATZ staff is also expected to abide by what Liston considers his greatest pet peeve: “Never use exercise as punishment.”

“It’s absurd to me you’re going to punish people with what you want them to love, and changing that thinking is essential to breaking 50 years of bad habits among coaches and trainers,” Liston says.

Nicknames, also, are not allowed at CATZ, a rule Liston attributes to simple respect. “You never know how someone feels about a nickname. Also, you’re allowing your entire coaching staff and kids to start calling each other names. And that can’t happen.”

Finally, CATZ staff is instructed to always listen to their patrons’ requests.

“You might have a great idea, but hearing their voice and allowing their input is the beginning of getting your client to ‘own it,’ of them taking it in and owning activity and owning this training session and loving it,” Liston adds.

FITNESS AND THERAPY: POINTS ON A CONTINUUM

|

| Jim Liston, PT, leads a group in “The Big Finish.” Liston says his community outreach efforts have helped drive the success of programs that encourage activity among youth in the Pasadena area. |

Liston asserts that therapy and performance training are simply two points along a continuum of physical activity, and at a certain point, the two begin to merge. Two thirds of the CATZ client base currently falls on the therapy side of the continuum, but Liston says he expects the center’s climbing enrollment in its sports training and performance programs to eventually outpace the physical therapy population.

“The CATZ side is growing rapidly, and though I feel the whole pie will get bigger, the CATZ portion of the overall revenue will continue to expand and eclipse therapy as a matter of percentage. In time we’ll see two thirds of our revenues come from the performance side and probably one third come from physical therapy,” Liston says.

In the meantime, Liston and Wentz strive to cultivate a sense of community they believe is a healing and positive force that therapy patients, children, and athletes of all ages can use to progress toward their goals. CATZ concludes each hour of workouts with “The Big Finish,” as a way to promote this sense throughout the facility.

“Sometimes it’s 6-year-old kids alongside professional athletes; it’s kind of ‘leave your ego at the door’ and we all come together and finish with ‘medicine ball hop,’ or jump up and scream, it really doesn’t matter,” Liston says.

“It’s something that’s engaging and fun, and everyone who was there for that hour of the day feels like they were part of that group.”

Frank Long is the associate editor of Rehab Management. For more information, contact .