|

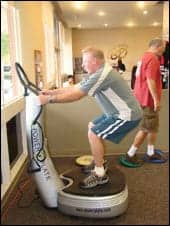

| A Nifty After Fifty client uses a device that stimulates bone mineral density with vibration. The fitness center was established to promote physical wellness for older adults. |

Avoiding age-related diseases may not be the secret to reaching one’s 100th birthday after all, according to a February 11 report from Boston University’s Boston Medical Center’s New England Centenarian Study. In the 739 centenarians studied, about one-third had been living with age-related diseases such as stroke, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes for more than 15 years. The secret to their longevity, researchers found, was avoiding disability.

This finding should come as no surprise to PTs, who work with geriatric patients to improve strength, fitness, and balance. They see firsthand how physical fitness contributes to the patients’ ability to live independently—and also influences mental acuity by directing blood flow to the brain.

Regardless of disease, muscle weakness is usually the reason a patient cannot get out of their chair. Addressing frailty means developing a program that strengthens these muscles. “If you can regress this muscle weakness, you have reversed, in large part, frailty,” says Sheldon S. Zinberg, MD, founder of Nifty After Fifty, Garden Grove, Calif, and author of the forthcoming Nifty After Fifty: A Guide to Better Fitness and Aging. “The idea being to die as young as you can, but as late as you can.”

TAILORED ROUTINES

Of course, there is no universal formula for a successful geriatric fitness program, so PTs must work with patients to individualize their care. For example, the exercises for a patient with acute cancer, diabetes, and an amputation would be decidedly different from those recommended for a patient with osteoarthritis, two joint replacements, and a vein-stripping in the lower leg.

|

|

| Strength training, customized exercise programs, and nutritional coaching can help seniors remain healthy and active through the course of their lives. |

“The word ‘exercise’ has one spelling, but how it is applied is extremely diverse,” says Timothy L. Kauffman, PhD, PT, founder of Kauffman-Gamber Physical Therapy, Lancaster, Pa, and coeditor of Geriatric Rehabilitation Manual, Second Edition (2007).

The initial patient evaluation is crucial to determine a patient’s individual goals and limitations. Kauffman begins by watching how the individual moves and then collects a detailed history. He observes the client’s range of motion, strength, circulatory response, balance, and ambulation. He also makes sure to ascertain the client’s personal, but realistic, goals for therapy. The idea is to make sure they are invested in their progress by setting attainable milestones.

“I ask them, ‘Why are you here? What is your chief complaint? What do you want to get out of this?'” he says. “I am very strongly oriented in thinking that the human potential to improve remains until the very end.”

At Nifty After Fifty facilities, fitness coaches, who all have degrees in kinesiology, develop a customized exercise program for each client based on an initial evaluation. The program usually combines supervised routines at the facility itself 2 to 3 days a week as well as exercises to do in the home.

Nifty After Fifty facilities use computerized Keiser pneumatic strength-training machines. Each client receives a “key” that they insert into each machine throughout their routines. The key tracks how many sets and reps they do on each machine as well as how much pressure they use. At the end of the session, the coaches download the information from the key, which gives them an accurate picture of the client’s workout.

“Every 2 to 3 weeks, we attempt to adjust it,” Zinberg says. “When possible, of course, we increase the intensity of the exercise programs. Sometimes, we just maintain them.”

On the nutritional side, coaches work with clients to determine the foods that they enjoy and those that they dislike. Using a computer program based on information from the Institute of Medicine, they devise a menu using the foods the clients like and then grade the nutritional content. They then suggest improvements to ensure that all the necessary vitamins are included. “If you say, ‘I’m just not going to eat that broccoli,’ then we recommend a supplement, but we prefer to do it through food,” Zinberg says.

The facilities also focus on developing mental acuity and preserving reflexes. For example, clients use a program called Happy Neuron for what Zinberg describes as “brain aerobics.” These exercises target memory and problem-solving skills. Nifty After Fifty also prescribes exercises to improve reaction time and offers a driving-simulation course.

Many clients take advantage of group classes, such as yoga or Pilates, as well as social events such as movie matinees that the facilities offer on Saturday mornings. These gatherings motivate clients socially as well, which is another way to keep them engaged. “It’s amazing how these people begin to interact with one another just while they’re exercising,” Zinberg says.

Often, this social aspect is the key to motivating clients to get out and exercise. Formal classes are just one way to fill this need. It can be as simple as two neighbors walking regularly together. Even televised or pretaped exercise programs, such as yoga videos, can be effective. “Generally, people are more motivated to exercise when they exercise with someone,” Kauffman says.

HOME WORK

While supervised routines in a facility or clinic are very beneficial, Kauffman notes that the home exercise component cannot be underestimated—even when elements such as doorway width or bed height are not ideal.

“Sometimes the home is less than ideal for rehabilitation to take place, just simply because of the constraints,” he says. “However, sometimes in the home, because a person is in a loving environment, the work that can be done is greater.”

Floor exercises and chair exercises are popular elements of home routines. For patients who live in harsh winter climates, the home also provides a safe exercise environment when icy sidewalks prevent outdoor walking. Some patients may enjoy walking in indoor malls or even working out at nearby gyms—but sometimes the snow and ice are too much of a deterrent. In these cases, creating a walking path from the front to the back of the home, doing Tai Chi in the bedroom, and even doing side steps by the kitchen sink are great ways to stay active.

“You can strength train very well by taking one step and stepping up and down on it, just like a stair climber,” Kauffman says.

The important thing to remember is that not all exercises have to be formal. Kauffman notes that just dancing to music can be a wonderful way to exercise. Even for these simple actions, however, PTs should help clients find the best way to move. For example, some patients present with both osteoporosis, which does not allow backward bending, and spinal stenosis, which does not allow forward bending. “So, you have two different disease processes in the same individual,” Kauffman says. “That’s where you have to individualize the care.”

FORWARD THINKING

While the recent report from the New England Centenarian Study indicates that more people have the potential to reach their 100th birthdays, Zinberg cautions that the prevalence of obesity and Type II diabetes in younger generations may have the opposite effect.

“This really casts a shadow on the likelihood of greater and greater longevity,” he says. “What one might see is the likelihood that we will live shorter lives than our ancestors for the first time in the history of this country because of an increase in obesity and Type II diabetes.”

Zinberg adds that this outcome is not necessarily inevitable, but that it needs to be addressed through a regimen that targets both physical and mental fitness. “The way to address it is with the mother of all disease management programs,” he says.

The future of gerontology research is bright, especially advances in stem cell research that may shed light on how to achieve better quality of life. However, Kauffman cautions that there will never be a cure for all pathology. “In the general public or press, people are looking for simple answers, and it’s not simple,” Kauffman says.

Still, encouraging both physical and mental fitness is the best way to ensure high-quality longevity. The key to developing a successful disease management program is to individualize the care and encourage geriatric clients to set realistic goals. “The most important question is not how long we live, but how we live,” Kauffman says. “It’s the quality of life, not the quantity of life.”

Nancy Lorcan is a contributing writer for Rehab Management. For more information, contact .

THE ROAD HOME

New thinking and advanced technology help stroke survivors stay out of nursing facilities.

The landscape for rehabilitation of geriatric stroke sufferers is being reshaped by innovations in mobility and electrostimulation technologies, and refined by clinical enlightenment in such areas as neuroplasticity. These research and engineering dividends have become central components of strategies that keep stroke sufferers in their homes and out of skilled nursing care.

“Studies are starting to show the earlier you begin stroke rehab, the better potential for an outcome,” says H. Richard Adams, MD, medical director of the Adult Brain Injury Rehab Program at Long Beach Memorial Medical Center, Long Beach, Calif.

Adams is a site director for the Locomotor Experience Applied Post-Stroke trial, a 5-year, $13-million study funded by the National Institutes of Health. He estimates 85% of geriatric strokes are triggered by a blood clot that originates within the brain or travels to the brain from the heart or carotid artery. Adams says the extreme degrees of hemiparesis and language impairment that can result from stroke ravage functional independence, but notes that advances in assistive technologies and electrostimulation have provided resources to hedge against the odds of a stroke survivor being placed into skilled nursing care.

“We’re working on improving a patient’s communications abilities and also teaching them compensatory strategies to use to communicate,” Adams says.

A communications lab within the facility where Adams works houses a variety of assistive equipment that matches patients to appropriate devices intended to help them address stroke-related deficits. Visual gaze systems that allow a user to control environmental systems that operate household lights, electronics, and call systems have made a difference to many patients, Adams says. He adds that talkback systems that construct words and sentences for patients with language deficits are also being used effectively.

Rehabilitation for foot drop—a condition often prompted by stroke—has also gotten a boost from a two-piece wireless device recently approved by the FDA, according to Adams. The device, he says, enables users to send electrical stimulation to a lower extremity and correct for the deficit. Though Adams considers the device costly, he says it helps maintain muscle tone and integrity and has proven particularly useful in treating older patients.

A stroke sufferer’s functional independence can be compromised by a significant deficit in mobility, heightening the likelihood that they may be moved into a skilled nursing facility, according to Adams. Helping to resolve these types of issues, he says, are lightweight wheelchairs that assist patients who may possess the cognitive skills to operate a conventional wheelchair but whose limbs have been impaired by stroke-related weakness or comorbidities such as severe arthritis. Scooters, too, Adams notes, are increasing in use by the geriatric population—a trend he says is likely attributable to the devices’ agility and decreased bulk.

Lingering problems with continence can cause care issues capable of stalling a return home for geriatric stroke survivors and driving them into skilled nursing care. Though home care for such conditions can be demanding, Adams suggests a close and connected effort between patients, their families, and the rehabilitation team can help avert confinement to a nursing home.

“It’s very difficult from a psychological standpoint for caregivers who are family members to work with bowel and bladder problems,” Adams says. He points out that caregivers are sometimes family members who, themselves, are elderly and unable to provide adequate physical assistance.

Well-crafted compensatory strategies can make the difference in keeping geriatric stroke survivors in their homes, Adams continues, and he acknowledges that adaptive equipment such as raised toilet seats, shower chairs, and extended hoses provides caregivers with a steady stream of devices to aid their efforts. Adams also points out that improvements in components of mobility—sitting and standing tolerances, transferring from bed to chair and from toilet to chair—can help improve bowel and bladder control to the highest functional level possible.

Frank Long is associate editor of Rehab Management. For more information, contact .