These functional methods provide a game plan for implementing standing tolerance activities with patients whose goal is to walk again.

by Alexa Boeker, MS, OTR, and Diana Hanley, MS, OTR

Why Standing Tolerance?

Among occupational therapists, it is a commonly held opinion that standing is the foundation of many essential daily occupations. Standing is a multifaceted activity, closely linked to functional endurance, balance, and upright posture. These abilities are often addressed as underlying deficits or precursors to functional mobility, activities of daily living (ADL), and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) performance,2 creating commonly held goals for many patients and families.

Within our own practice, more often than not, patients with a wide variety of diagnoses identify “being able to walk again” as their most important goal. While ambulation is meaningful for many, we must first prioritize the underlying skills of standing tolerance and associated factors as important steps toward this ultimate goal. It is also important to note that functional standing tolerance as preparation for mobility is associated with increased independence and reduced burden of care for family members as well as staff members at facilities.

Adding Function

While standing is essential, the way that it is addressed in practice can impact overall functional performance and outcomes. Too often, standing activity in a treatment session is addressed in isolation, lacking purpose or relevance to individualized goals. Research shows that individuals with a wide variety of diagnoses experience greater outcomes when using purposeful activities compared to rote activities.1 We have found better buy-in from patients and families when incorporating meaningful, functional session tasks. Activities that are intrinsically motivating become memorable experiences, allowing patients to more easily recall specific education to carry over to future scenarios. Research has shown that patients who participate in purposeful standing activity, as compared to rote activity, also endure longer standing trials in treatment sessions.1 And all of this provides patients with better preparation to perform these activities in their home.

Putting It Into Practice

Just as the topic of functional standing applies to a wide variety of patient diagnoses, it is also addressed in various settings across practice, such as inpatient rehab, inpatient acute care, and skilled nursing facilities, to name a few. Most therapists have seen firsthand the challenges of implementing functional activities into sessions when given limited time, access to equipment, or space. The following are examples of both common and commonly overlooked spaces in which to incorporate functional standing tasks:

- sink

- bedside table

- closet/clothing rack

- elevated bed/rail

- window ledge

- mirror

- white board

- grab bar in bathroom

- standing computer

- elevated mat tables

- door

- overhead cabinet

- storage shelves

- room divider curtain

- nurse’s station

- dining room table

- Christmas tree (at holidays)

- kitchen counter

- washer/dryer

- dresser

- hall rail

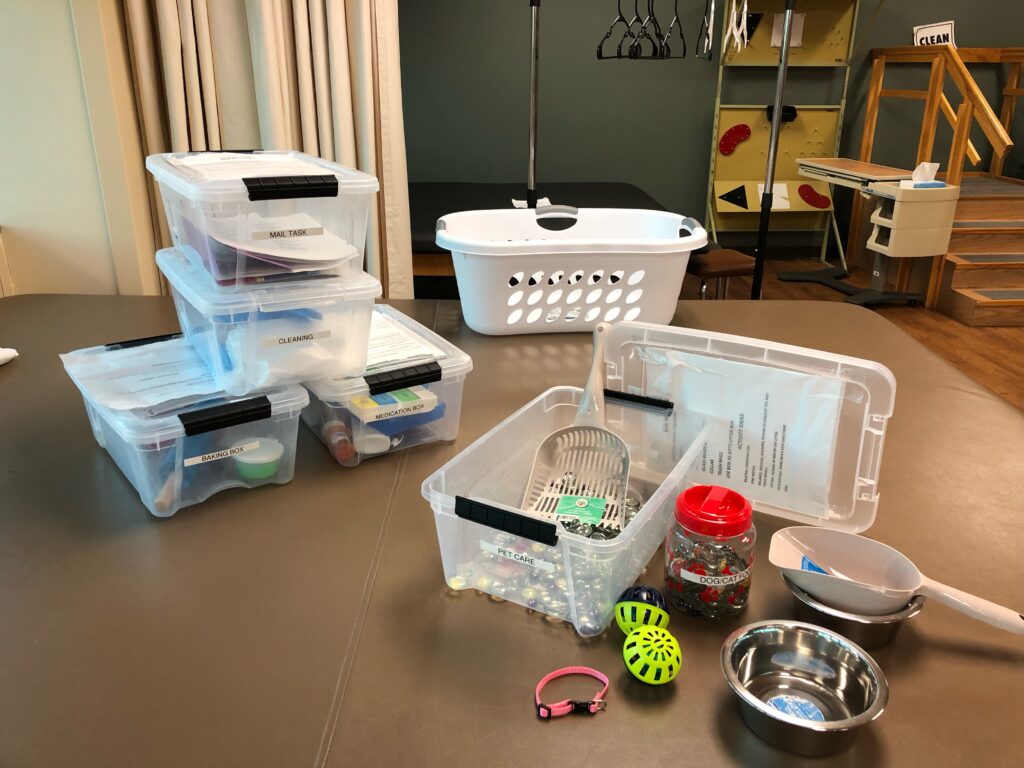

In addition to spatial limitations, lack of readily accessible equipment and materials can be a barrier to implementing functional (standing) activity in the clinic. In our setting, therapists have created ADL/IADL kits. These include storage bins with lids housing themed items to simulate everyday tasks. We store all kits in our therapy gym, where they can be easily pulled off the shelf for use in various units of the hospital.

Examples of kits in our facility include: cleaning, pet care, letter writing, medication management, baking, and a tool kit, among others. Many items included were donated by staff members or purchased at a dollar store. These kits were designed to address fine and gross motor coordination skills, activity tolerance, balance, and cognitive deficits, which can all be combined with standing activity. Each kit also includes a printed list of various treatment ideas for reference, designed for quick implementation. Since using these kits, therapists have reported improved incorporation of function into sessions, as well as reduced prep time required.

How to Grade Standing Tasks

One essential aspect of creating an individualized treatment session involves gradation of activity. Grading an activity may allow practitioners to use the same activity for multiple patients, but change aspects of it to ensure a just-right challenge for the optimal participation and success of each specific patient. Just like any activity, functional standing can be graded appropriately depending upon the patient’s current physical status.

For example, let’s use a functional standing laundry task as a session activity. The following ideas begin with a basic task and increase in difficulty:

- Standing statically to walker and verbally giving therapist instructions for sorting laundry, while patient focuses on general standing tolerance and balance with bilateral upper extremity support;

- Sorting laundry by color/type at a table while standing, maintaining one upper extremity support at a time for balance;

- Standing and folding laundry using bilateral upper extremities with use of 2-wheeled walker or tabletop for intermittent upper extremity support;

- Standing in place while placing laundry items on hangers and reaching minimally outside base of support to hang them on a rack in front of the patient;

- Transporting laundry items across a room with or without assistive device, to hang in the closet on a rack;

- Retrieving laundry items from the floor or various surfaces in a room, then folding/hanging and putting them away; or

- Simulating full laundry task with use of washer and dryer.

For any of these tasks, you may also vary the number of items or the total time spent standing for completion or distance completed for incorporated functional mobility.

Examples Of Measurable Standing Tolerance Goals

- Patient will stand for 2-minute activity while maintaining O2 saturation at 92% or above, in order to improve functional activity tolerance for dressing tasks

- Patient will maintain standing position with fair (-) balance in order to complete toileting tasks with maxAx1

- Patient will tolerate standing with contact guard assist to fold 5 laundry items prior to seated rest break

- Patient will tolerate 15 reps of shoulder flexion with hemiplegic upper extremity in standing position, in order to simulate window washing for return-to-work task

- Patient will tolerate standing grooming routine at sink with standby assist, with one seated rest break

Quick Reference Guide for Functional Standing Activity

As you plan how to incorporate functional standing activities into sessions with your patients, you can refer back to this list of options:

- grooming at sink

- item retrieval/restoration throughout room or from closet

- laundry tasks (folding, hanging, sorting)

- washing windows/tables/counter/mirrors

- vacuuming

- sweeping

- bed making

- washing dishes/loading washing machine

- kitchen mobility/item retrieval from cabinets/fridge

- simulated meal prep

- grocery tasks

- decorating (hanging pictures)

- writing grocery/errand list on vertical white board

- opening/closing blinds

- games (corn hole/bags, golf, basketball, bowling)

- simulated fishing

- simulated work tasks

- portable work sample test for simulated “handyman” tasks

- typing at standing keyboard

- childcare tasks (standing at changing table/carrying baby)

- pet care tasks (feeding and watering, clean-up and changing litter box).

Alexa Boeker, MS, OTR, is an inpatient occupational therapist with experience in inpatient rehab and skilled nursing, specializing in the treatment of patients with stroke and brain injuries at Springfield Memorial Hospital in Springfield, Ill.

Diana Hanley, MS, OTR, is a Level III occupational therapist with Springfield Memorial Hospital, specializing in the treatment of patients with stroke and brain injury in inpatient rehab. For more information, contact [email protected].

Main Photo: 100656705 © Katarzyna Bialasiewicz | Dreamstime.com

References

1. Flinn N. Clinical interpretation of “effect of rehabilitation tasks on organization of movement after stroke.” Am J Occup Ther. 1999;53(4):345-347. doi:10.5014/ajot.53.4.345

2. Hsieh C, Nelson DL, Smith DA, Peterson CQ. The comparison of performance in added-purpose occupations and rote exercise for dynamic standing balance in persons with hemiplegia. Am J Occup Ther. 1996;50(1):10-16. doi:10.5014/ajot.50.1.10