By Frank Long, Editorial Director

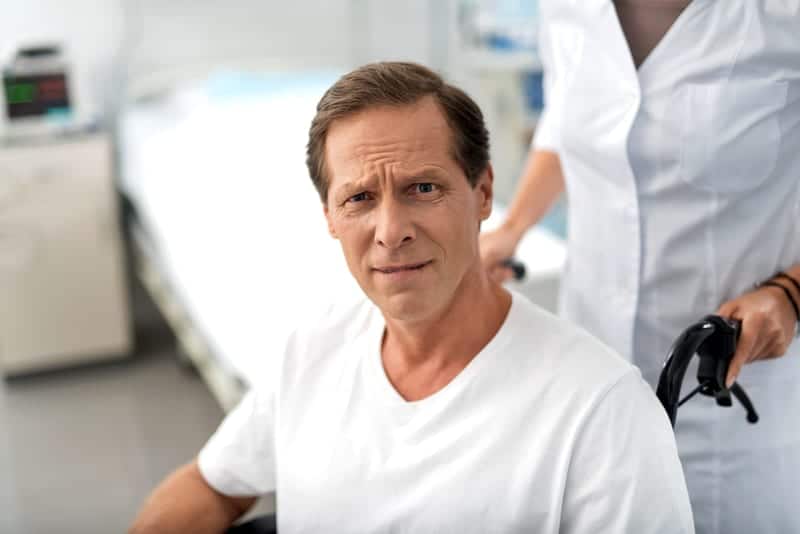

You didn’t die. You battled COVID-19 in intensive care for more than a week. You were on a ventilator but pulled through. Now you are disabled.

This will happen to a significant number of people who discharge home after fighting COVID-19. It is typical of the course that post-intensive care syndrome (PICS) takes by creating or worsening physical impairment as well as causing cognitive and psychological impairment among patients who have been critically ill.1

Neuromuscular weakness is the most common form of physical impairment that individuals acquired during a stay in the ICU, with more than 25% having poor mobility, recurrent falls, or quadri or tetra paresis.2

Physical symptoms often resolve within 12 months after discharge from an acute care setting. However, research shows that ICU-acquired weakness can last as long as 24 months.1,2,3,4

A public health crisis

With the CDC reporting more than 800,000 cases of COVID-19 in the U.S. as of April 21, conditions seem ripe for a surge in the number of people who will emerge from intensive care with PICS. In fact, James M. Smith, DPT, professor of physical therapy at Utica College, Utica, NY, says PICS will be the next public health crisis related to COVID-19 and that patients as well as their families will fall into its grip.

“We’re going to see people coming back from the hospital after experiencing COVID 19, and they’re going to have these physical problems. That’s a burden not just on them, but on their family,” Smith says in an April 21 report by Utica, NY, media outlet WKTV.

While neuromuscular complications are common during prolonged stays in the ICU and mechanical ventilation certain organs are also put in danger with the lungs, kidneys, and brain among organs that most commonly fail.5

The road back

Hospitals continue to treat large numbers of COVID-19 cases, so healthcare professionals from the ICU setting and all along the continuum of care should probably be asking themselves how can PIC be minimized. One approach detailed in a recent study shows that early physical and occupational therapy during critical illness are the best evidence-based target interventions for reducing the long-term physical complications that acquired lung injury survivors experience.2

Once a patient leaves the inpatient setting, Smith observes, COVID-19 survivors will have physical problems that include decreased function, weakness, and difficulty walking. While those individuals may find ambulation is a challenge, it will be only one challenge among many.

“They’re going to have mental health problems such as anxiety, post traumatic stress disorder, and depression, and they’re going to have cognitive problems with clarity of thought,” Smith adds.

Simple healing

For people affected by PICS who want to move past its debilitating effects there is at least one approach that is both simple and effective, according to Smith. He recommends walking as one way for COVID-19 survivors to address the lingering effects of PICS, noting that it improves heart and lung performance and benefits the musculoskeletal system.

“Physical activity and exercise reduces the risk of psycho-emotional problems like depression, so right off the bat become active,” Smith says. “If you haven’t been active, getting active is going to help with some of those distressors, and it’s going to give you a better foundation,” he adds.

The Cleveland Clinic also outlines several approaches the healthcare team may use to address PICS. Among the non-invasive treatments recommended is to utilize physical therapists and occupational therapists in reducing weakness and improving physical function after a stay in the ICU. The clinic also recommends pulmonary or cardiovascular rehabilitation in addition to a healthy diet, adequate sleep, and follow-up counseling when emotional symptoms are present.

References

- Rawal G, Yadav S, Kumar R. Post-intensive Care Syndrome: an Overview. J Transl Int Med. 2017;5(2):90–92.

- Fan E, Dowdy DW, Colantouni E, et al. Physical Complications in Acute Lung Injury Survivors: A 2-Year Longitudinal Prospective Study. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(4):849–859.

- Hermans G, Van Mechelen H, Clerckx B, Vanhullebusch T, Mesotten D, Wilmer A. et al. Acute outcomes and 1-year mortality of intensive care unit-acquired weakness: A cohort study and propensity-matched analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:410–20.

- Fan E, Cheek F, Chlan L, Gosselink R, Hart N, Herridge MS. et al. An official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice guideline: the diagnosis of intensive care unit-acquired weakness in adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:1437–46.

- Latronico N, Tomelleri G, Filosto M. Critical illness myopathy. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24:616–22.