PHOTO CAPTION: Plyometric boxes at varying heights can be used in circuit training and to provide maximum stability and durability when performing tasks that mimic work conditions.

Preparing clients to return to physically demanding work often requires a targeted, intensive simulation program.

By Eric Shifley, PT, MPT, COMT, CertDN

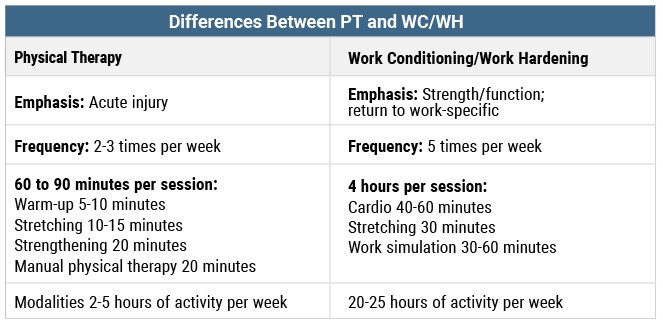

Returning an injured worker back to work can be one of the biggest hurdles for a physical therapist. Physical therapy rehabilitation is generally effective for workers not performing manual labor—office work, sales, education, etc—who make up about 80% of the injured population. For the remaining 20%—manual laborers such as carpenters, ironworkers, roofers, etc—physical therapy (PT) rehabilitation often falls short, leaving them unable to return to their occupations.

For workers who find themselves in this situation, work conditioning/work hardening (WC/WH), a lesser-known rehabilitation option, is recommended. The problem is many physicians and even workers’ compensation professionals do not know about this option or understand the difference between it and physical therapy.

Recovering Injured Work Athletes

One successful WC/WH program in Illinois was developed based on extensive research and input from orthopedic surgeons, physical therapists, athletic trainers, exercise physiologists, and bio-mechanists to safely return injured workers back to the workplace. It is a customized program based primarily on the client’s current level of function with an identified return-to-work end goal in mind. The program is usually 4 to 6 weeks long, with 4- to 5-hour sessions per day (though modifications can be made to fit a patient’s needs).

The referral path for an injured worker into the program typically follows PT treatment and if they have reached a plateau in physical therapy, has insufficient strength/tolerance compared to his/her prior functioning level, and/or cannot meet their occupational physical demand level because of remaining deficits.

When treating these individuals, it is important to view injured workers as work athletes. Whether they work as a first responder, in construction, in maintenance, or on an assembly line, they should be viewed as an athlete, as many need cardiovascular endurance, strength, stamina, and appropriate body mechanics, just like a sports athlete.

Recommended Regimens

With any program, it is wise to start with a warm-up followed by a stretching routine. Stretching may incorporate stretch straps to appropriately elongate upper and lower extremity muscle groups without placing undue stress on joints to achieve the desired stretch. They can rely on the user’s own body weight to assist. Foam rollers can be used to open postural changes, mobilize the spine, or roll out tight muscle groups.

Many injured work athletes’ professions, such as firefighting or construction, require physical activities. To help mimic the actual job function, strength and cardio training via circuit routines should be involved in any program. For example, a firefighter will start with various weight training exercises. Some options offer a variety of strength training exercises in one piece of versatile equipment.

Like for firefighters, weight training for construction athletes requires pushing and pulling exercises. Cable column machines that can be adjusted to various heights as well as free weights are key to simulate lifting from the ground, the bed of a truck, or overhead. It’s helpful to use a machine that offers a variety of adjustments and angles to help mimic numerous working conditions.

Weighted kettlebells also offer a way to strengthen the lower back as well as help mimic the right form to pick up and put down weighted objects. A firefighter, toward the end of training, might also don his or her gear and substitute a fire hose with a weighted battle rope. These are available from multiple brands and can be used for a variety of fitness exercises.

Firefighters may need more variety in their recovery plan, especially those whose assignments require them to be on their feet for extended periods of time. Stationary bikes, rowing machines, stair climbers, and elliptical machines can be incorporated to simulate the various conditioning requirements to be prepared for the front lines.

Manufacturing athletes, along with first responders and those in construction, will need to incorporate carrying exercises. Loading boxes with weight or carrying free weights is highly important to the plan to simulate work responsibilities. The simulations can be done on level surfaces, incorporating plyometric platforms, or even while walking on a treadmill. Plyometric boxes at varying heights provide maximum stability and durability to help mimic these conditions.

In a study on the importance of improving injured workers’ lifting abilities, 94.9% of patients in the Illinois program achieved the medium physical demand level (able to lift 50 lbs occasionally, or better) and 45% met the heavy physical demand level (able to lift 100 lbs occasionally) in order to return to work.

Getting Results

Most patients participate in a WC/WH program for 6 weeks or less. Some people might stay in the program for more than 6 weeks if they have extenuating circumstances such as multiple surgeries, occupations with very heavy requirements, or multiple co-morbid conditions.

The main reason for limiting involvement in this type of program to around 6 weeks is that this is the point at which physical demand levels tend to plateau. Beyond that timeframe, there does not seem to be a significant improvement in function. People may improve occasionally past 6 weeks, but generally that occurs less frequently.

In addition to assessing patients upon graduation from the Illinois program, those running the program also assessed patients at 1 and 2 years post-program completion to determine if their improved physical abilities increased their return-to-work rates. The results showed 97% of those in the program returned to work and half returned to their former occupation. Reinjury rates were rare and occurred less frequently with greater physical abilities.

These results validate the approach of these types of programs: improving outcomes by increasing physical capabilities that result in higher return-to-work rates and lower reinjury rates.

Overcoming Cost Challenges

WC/WH programs have financial benefits as well as recovery benefits. Currently, physicians prescribe PT with the expectation that insurance companies will continue to reimburse for those services if the patient has not improved sufficiently to return to work. Yet based on national statistics, injured workers would be better served by a safe and appropriate transition from physical therapy to a WC/WH program because of the program’s return-to-work success rate and end objective.

This is particularly important in today’s changing healthcare marketplace and with the rising cost of workers’ compensation insurance for employers. According to the Insurance Information Institute, the annual average rate of increase in workers’ compensation medical care costs was 3.9% from 1991 to 1995. Since then, the rate of increase has more than doubled and, in most years, was more than twice the rate of increase in the medical Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Numerous strategies have been tried to decrease employer costs, but few have provided real cost relief. One of the major problems is that few people understand the difference in handling patient care and cost structure under workers’ compensation cases compared to regular group healthcare.

Workers’ compensation provides “indemnity benefits” that can include wage replacement and disability benefits, in addition to medical cost coverage associated with treatment. Because the two are so integrally related, trying to lower costs in one without the other has not worked and overhauling both has proven too cumbersome for most states, resulting in virtually no relief for employers. Consequently, WC/WH programs have been developed and used successfully.

With the proven success of these programs and the continued malaise within many states’ workers’ compensation programs, incorporating a WC/WH element into the system not only makes sense, but ultimately will save states money, return more workers to their jobs, and help ensure those who return to their jobs are physically able and less likely to become reinjured. RM

Eric Shifley, PT, MPT, COMT, CertDN, is a clinic director at ATI Physical Therapy in Chandler, Ariz. He has a Master of Physical Therapy degree from Midwestern University. For more information, contact [email protected].